Since the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in 1928, bacteria have constantly evolved new ways to resist the effects of antibiotics, so that they are not killed, or their growth is not stopped.

Currently more than 50,000 people diein Europe and the US every year from infections that don’t respond to conventional antibiotic treatments. And if current trends continue, all of our antibiotic medicines could become ineffective within the next few decades.

"The twofold problem is that the discovery of new antibiotics is not economically viable. Therefore, we need to think of a new way of doing it. So the problem we have now is only going to get worse because there's no new drugs through the pipeline. So that's number one," said Chris Dowson, professor of microbiology at the University of Warwick, and trustee of Antibiotic Research UK.

"And then secondly, there's probably more people talking about the problem than there are people being trained. And so as we all who are in the field get older and retire, training the next generation is as much of a problem as the lack of drugs."

One way of potentially combatting this disturbing trend is to use bacteriophages – a type of naturally-occurring virus capable of killing bacteria.

Now, a team of researchers from Université de Montpellier, France, and University of Pittsburgh, USA, have discovered that combining bacteriophages with conventional antibiotic treatments could make them even more effective bacteria killers.

The study is published in the journal Disease Models & Mechanisms.

Read more about antibiotic resistance:

- The nine most dangerous antibiotic-resistant bacteria

- Is antibiotic resistance really as bad as climate change?

The team decided to focus their efforts on Mycobacterium abscessus, a relative of the bacteria that cause tuberculosis and leprosy that is resistant to many standard antibiotics.

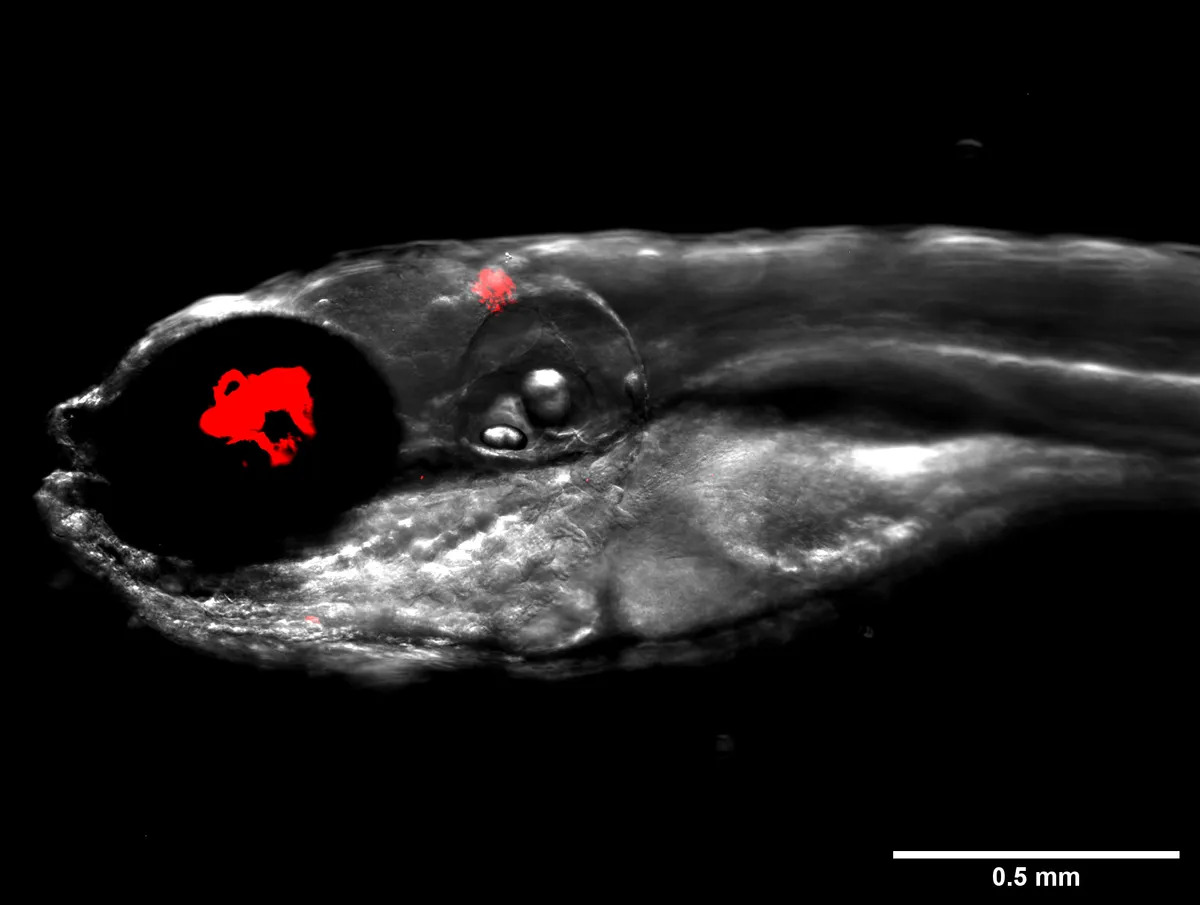

As M. abscessus is particularly dangerous to patients with cystic fibrosis, they infected zebrafish carrying the key genetic mutation that causes the disease with the bacteria and went about testing the ability of a bacteriophage to combat it.

After screening 10,000 bacteriophages, the team found one candidate, which they named ‘Muddy’, that was capable of efficiently killing bacteria in a petri dish. They then infected zebrafish with M. abscessus and monitored them for 12 days.

They found that the fish treated with Muddy had much less severe infections and were twice as likely to survive – 40 per cent of them survived compared to 20 per cent of untreated fish.

They then treated fish with a combination of Muddy and rifabutin, an antibiotic used to treat M. abscessusinfection that is similar in effectiveness to the Muddy treatment. This time the survival rate rocketed to 70 per cent and the fish suffered far fewer abscesses.

“We need clinical trials, but there will be many other questions to be answered on our way there. And zebrafish provide a very helpful tool for advancing these questions,” said Prof Graham Hatfull from University of Pittsburgh, USA.