Heart failure affects over 10 million people in the US and Europe every year and the outlook for patients is often bleak. Medication can only control the condition for so long and most patients require a complete heart transplant. If your heart slowly failing isn’t scary enough, the number of donor hearts that become available each year is tiny compared to the number of people waiting for one. For some patients, their size or blood type means the chances of finding a donor heart are virtually zero.

Attempts have been made to design artificial hearts since the 1950s, with little success. Many tests of artificial hearts over the years have involved seeing how many days – and it was often days – some poor animal could survive with one installed instead of its natural heart.

The complex system of artificial pumps and valves – required to beat over 100,000 times a day and tens of millions of times a year – get worn out, meaning mechanical hearts can start to fail even more rapidly than the diseased hearts they replace.

The few artificial hearts that have been approved for human use are currently only ever used as a last resort, to buy a patient time before a real transplant. Patients have to wear cumbersome power boxes at all times, and wiring runs in and out of their chests, leading to infections.

Read more about heart disease:

- Artificial intelligence could create heart attack early warning system

- Injectable hydrogel could help to repair damage following heart attacks

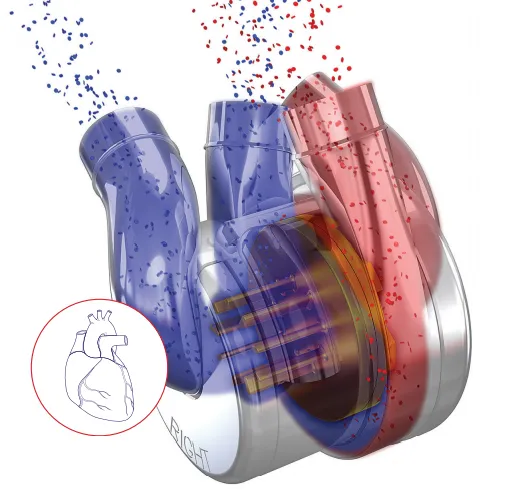

But a completely new design, known as BiVACOR, could revolutionise the use of artificial hearts and the way heart failure is treated. Instead of trying to replicate the way a real heart pumps, the device uses a single spinning disc to drive blood to the lungs and body. With the high-tech rotary pump levitating between magnets, there’s virtually zero mechanical wear. The lack of other moving parts means the rest of the heart can be made from ultra-robust titanium.

As well as its state-of-the-art levitating disc technology, the BiVACOR heart can adapt its output to the physiological demands of the patient (so it’ll pump faster during exercise) and can be made small enough to fit into a child. It’s also hoped that the device can one day be combined with wireless charging technology, meaning that the battery could also be implanted into the patient, instead of carried externally.

BiVACOR is the brainchild of Dr Daniel Timms, who began developing artificial hearts when his father Gary, a plumber, suffered a heart attack in 2001. When the problem of heart transplant shortages became clear to him, Timms – still a student at the time – started working on a prototype using 3D printing and plumbing equipment.

“We had no money to do anything like animal studies, that was just way too expensive. So my dad and I built a circulation system that replicated the human body,” says Timms, now chief executive of BiVACOR Inc. and an expert in cardiac transplant technology.

“We’d just go to Bunnings, our large hardware store here in Australia, and build up a circulation loop to test to see if it was providing good flow and pressure to the various areas of the artificial body that we created. Then we refined the devices from there.”

Back in 2001, spinning disc technology was in its infancy, but it was being used in implants that help blood flow in damaged areas of the heart. Timms’s idea was to take that technology and use it to design an entire heart from scratch.

“Effectively everyone had given up on making a complete total artificial heart,” he says. “Instead they were making these little devices that could be placed, say, in the left side only, and were just starting to use spinning disc technology. My approach was: well why don’t you apply that to a total replacement heart?”

The first artificial heart implantation was conducted in 1969 at the Texas Heart Institute, in Houston. When the patient survived for 64 hours without the heart he was born with, it was seen as a success; hopes were high that artificial heart transplants would become commonplace in the decades to come. But it simply hasn’t happened. Over half a century later, cardiac doctors are seeing more patients with heart failure every year, but are still waiting for a device that can reliably do the job of the organ beating away constantly in our chests.

Read more about health:

- A national screening programme ‘could prevent one in six prostate cancer deaths’

- NHS patients to swallow miniature pill-sized cameras to diagnose bowel cancer

BiVACOR has once again raised hopes that artificial hearts could put an end to the fraught and often futile search for donor hearts. The new design has not only raised millions of dollars in funding, but has also has gained support from the Texas Heart Institute, which leads the world in cutting-edge cardiac healthcare.

The design’s great promise is arguably that it’s not at all like an actual human heart, says Timms. “It’s a bit like heavier-than-air flight. Mother Nature gave birds flapping wings with bones and tendons and muscles. When we tried to do that in the early days of flying it really didn’t work very well. It wasn’t until we stopped trying to emulate birds and developed propellers and engines that we got off the ground.”

Since 2019, BiVACOR has been working with NASA, using their expertise in building ultra-reliable hardware for situations where failure means certain death. The device has been tested in a cow, which reportedly not only remained alive, but was also able to run on a treadmill, as well as other animals. And last year, after decades of development, doctors temporarily fitted BiVACOR devices into human patients undergoing heart transplant operations, as a first step towards human trials. Custom-made devices, tailored to the patients’ anatomical dimensions, were fitted to see if they’d work, before real donor hearts were implanted.

The company is now working towards its first proper human trials. The plan is to implant the devices into patients who can’t find a suitable heart donor, for three months, and monitor how they perform. Long term, it’s hoped that BiVACOR hearts can replace the total function of the patients’ hearts and offer hope to the millions of people who are waiting or unsuitable for heart transplants. If successful, it will end one of the great challenges of biomedical engineering.

“I had no inclination that it would turn into what it’s turned into now, none at all,” says Timms. “It was just a crazy idea that I thought somebody else must have already had, or that might move the field along and then somebody would take it from there.”