The movement of vertebrates from water to land was an iconic step in the evolutionary timeline. Now, research by a team at Harvard University has found that a small genetic change may have been all that was needed to allow a fin to develop into a limb.

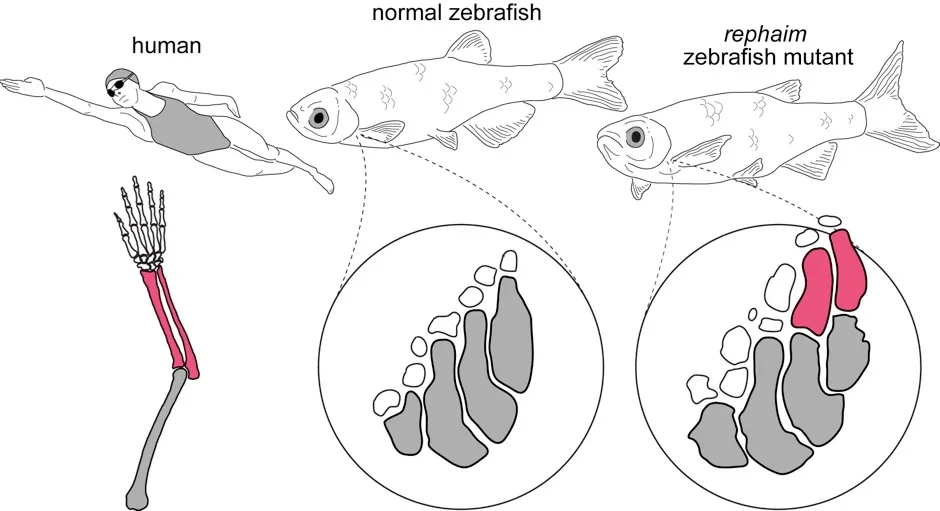

The researchers were investigating the mutations that can affect the pectoral fins of zebrafish. Unlike limbs, which have complicated bone structures and numerous joints, zebrafish fins are fairly simple. The team discovered that a small genetic mutation caused the pectoral fins to develop a more limb-like pattern, with additional bones, along with muscles and joints.

Read more about fish:

“It was a little bit unbelievable that just one mutation was able to create completely new bones and joints,” said Dr M Brent Hawkins, the lead author of the study.

Analysis revealed that mutations in either of two genes, vv2 and waslb, can independently cause this change.

“You didn't need to have a mutation in the muscle gene, a joint gene, and in the bone gene; the system is coordinated such that whatever our change is, it’s able to push all these things together in unison,” said senior author Dr Matthew Harris, associate professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School and orthopaedics at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Zebrafish belong to the teleost group of fish. It’s a diverse lineage, with more than 30,000 species, including eels, goldfish, mackerel, salmon, clownfish, anglerfish and seahorses. Despite the variety of body shapes, sizes and habitats seen in teleost fish, their pectoral fins are all surprisingly similar and unchanged.This research suggests that fish – like teleosts – who were previously thought to have lost the mechanism to evolve limbs, may actually retain a dormant ability to form them.

The development of limbs in tetrapods (four-limbed animals, including amphibians, reptiles, dinosaurs, birds and mammals) was an essential part of evolution, as it allowed vertebrates to emerge from the water and start walking on land.

The fin-to-limb transition led to the ancestral fin becoming more elaborate, and evolving many bones that fit together end-to-end. From the same ancestral starting point, the teleost fin became simpler; there are no bones fitting together end to end, instead there are ‘proximal radial’ bones, arranged side-by-side at the base of the pectoral fins.

The scientists were not able to establish whether the new bones in the mutant zebrafish would impact on the locomotion of the fish, but that will be the next step in the research. “Normally, the structures are not present to allow for the articulation required for movement on land,” said Harris. “It'd be very interesting to see, for example, if we put our mutant on a platform, whether they would have an adjusted gait.”

Read more about prehistoric animals:

- Prehistoric scorpion one of the first animals to scuttle on dry land

- Prehistoric amphibian terrorised early dinosaurs

- The walk of prehistoric life

Reader Q&A: Do fish drink?

Asked by: Angela Cobb, Leicester

Depending on where they live, fish either drink a lot or pee a lot. In the sea, a fish’s body is less salty than its surroundings, so it loses water across its skin and through its gills via osmosis. To stop themselves dehydrating, marine fish drink masses of seawater and produce a trickle of concentrated urine.

When migrating fish like trout and salmon move into rivers and lakes, they face the opposite problem and risk absorbing too much water until eventually their cells begin to swell and burst. To avoid this, they switch from being heavy drinkers to plentiful urinators.

Read more about fish: