A good story can pull on the heart strings, but new research shows just how much a captivating narrative can affect our bodies. So much so that storytelling could one day be used to assess consciousness in coma patients.

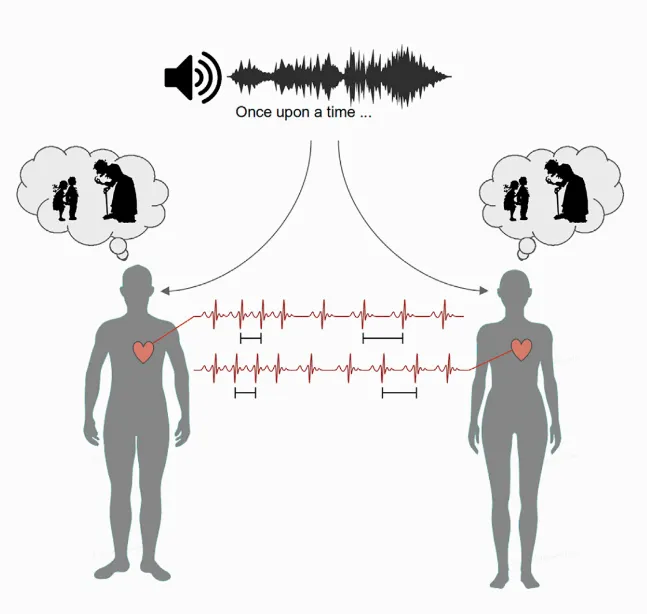

Published inCell Press, a new study shows how individuals who listen to a story all experience the same fluctuations in their heart rate, putting them in synchronisation with one another.

By monitoring these changes, researchers can tell whether a person is paying attention or not. Also, those who synchronised more were also able to remember more of the story afterwards.

The next step for the team was to find out what happened to the heart rate of patients with disorders related to consciousness, like those in a coma or persistent vegetative state, when they listened to an audiobook.

After listening to a children’s story, patients had lower rates of heart synchronisation than healthy people. This was to be expected. But, what was a surprise for the researchers was, on a second examination six months later, some of the patients who'd had higher levels of synchronisation had regained some consciousness.

Read more about storytelling:

- Storytelling reduces pain and stress in hospitalised children

- "Computers are not as smart as you think they are": The struggle of teaching AI to tell stories

In one case, a patient that initially was limited to just following a mirror with their gaze, was at the six-month point able to establish functional communication with doctors.

"We try to quantify the improvement of the patients' state," said neuroscientist Dr Jacobo Sitt, a co-senior author of the new research paper.

"Please keep in mind that the results on the patients are basically a proof of concept. Further work is needed to really assess the true usefulness of these tests on the clinics.

“This study is still very preliminary, but you can imagine this being an easy test that could be implemented to measure brain function. It doesn’t require a lot of equipment. It even could be performed in an ambulance on the way to the hospital.”

In assessing the link between the story, the brain and the heart, participants were played an audiobook of Jules Verne's20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

"When people listened to the story in our experiment, they sit in a small sound-damped room with all the sensors on," explained cognitive scientist Dr Jens Madsen, who led the research.

"The first thing that happens is we perceive the sound through our ears and low level features of the audio.

"Whether the narrator is talking loudly or softly, fast or slow, etc. This all affects how our brain responds to the stimuli.

"Then the processing moves up to a higher level like identifying words, sentences and finally meaning of the story."

Prior research has shown that at live events or loud concerts, the audience's heartbeat and breathing can synchronise.

Read more about the heart:

- Regularly drinking coffee may help to protect your heart

- The surprising science of why your heart doesn’t tire like other muscles

"If sounds are loud, our brain responds stronger than for weak sounds," explained Madsen. But for the lower level features, like how slowly the narration moves, the researchers didn't expect a direct effect on heart rate.

"This makes our finding just the more surprising, because we can’t directly explain the difference in synchronisation between people based on some low level property of the story."

Another interesting finding that came from the new research was the lack of impact listening to a story had on breathing.

"I was personally surprised that breathing didn’t synchronise [between individuals listening to the story]," said Madsen. "One could imagine people gasping or breathing heavily during moments of tension-release. But that wasn’t the case.

"Breathing is something that we have direct control over, contrary to our heart rate, so how we personally breathe could mask any stimuli driven effect, but we don’t know yet.

"We do however know that there is a connection between breathing and your heart rate, e.g. from meditation and other practices."

The researchers say that their next task is to understand what drives the synchronisation in heart rate. Then, they can start to build tools for clinics.