Conservationists have accurately recreated the Culloden battlefield using electronic mapping techniques, 275 years on from its last battle.

Experts say the new technology gives “the most detailed understanding” possible of how the landscape looked in 1746, when the final Jacobite Rising “came to a brutal head in one of the most harrowing battles in British history”.

Culloden, near Inverness, hosted the final fight of the rebellion where the army of Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie) was defeated by a British government force under William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland.

Jacobite supporters had sought to overthrow the House of Hanover and restore the House of Stuart to the British throne.

But on 16 April 1746, in the last pitched battle on British soil, around 1,500 Jacobites were slain within an hour, crushing the revolt.

Read more archaeological discoveries:

- Women’s skilled manual work was a “crucial” part of ancient farming societies

- Roman city revealed in 'astonishing level of detail' by radar technology

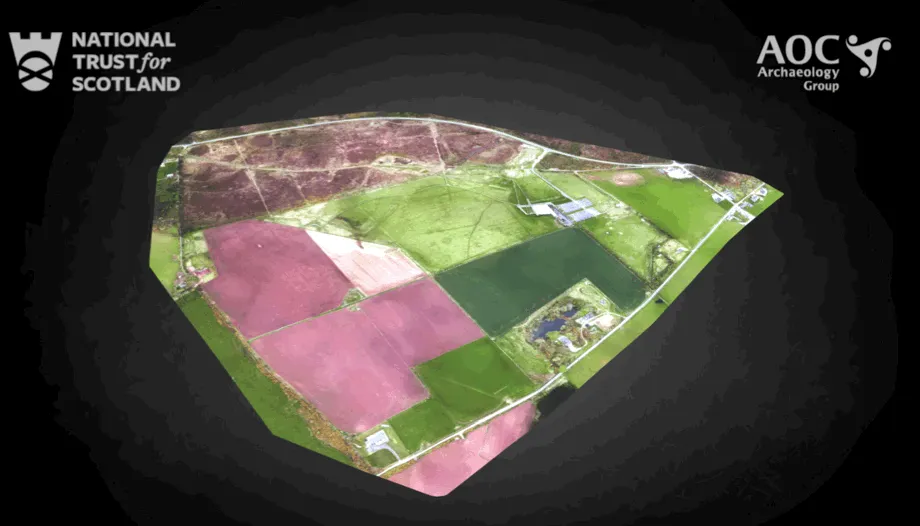

Experts used laser scans and Lidar (light detection and ranging) technology to create highly detailed topographical maps of the Culloden battlefield, which could take them back in time to view the landscape as it was on that fateful day.

“These maps give us the most detailed understanding currently possible of how the landscape looked in 1746," said Derek Alexander, the National Trust for Scotland's (NTS) head of archaeology.

“Thanks to 21st-Century technology, we can use these to get a feel for what soldiers on the battlefield would actually have been able to see of their opponents, their positions and their weaponry.

“In terms of understanding the tactics and the outcome, it’s a really powerful tool.”

The NTS is currently bidding to get the Culloden battlefield world heritage site status.

If the application to UNESCO is successful, it would become the seventh heritage site in Scotland, joining the Antonine Wall, the Heart of Neolithic Orkney, New Lanark, the Old and New Towns of Edinburgh, St Kilda and the Forth Bridge.

The trust says the site is under “greater threat than ever from developments” including housing and commercial projects.

The new maps have been created by AOC Archaeology to mark the 275th anniversary of the battle, and the maps include layers showing where archaeological excavations have happened over the years and where items have been found, said the trust.

“These maps aren’t just for the past, they’ll also help us to protect Culloden for the future," said Raoul Curtis-Machin, operations manager at Culloden.

“Their detailed information gives us a clear understanding of how the site has been altered through building and development over the centuries, all of which is invaluable as we strive to retain all that is special about this site that is of such significance to Scotland’s story.”

Reader Q&A: Why do we have to dig so deep to uncover ancient ruins?

Asked by: Nikkola Furfaro, Australia

There is a survivorship bias at work here: buildings and monuments left exposed on the surface don’t last very long. Humans steal the best bits to reuse in other buildings, and erosion wears everything else to dust. So the only ancient ruins we find are the ones that were buried.

But they got buried in the first place because the ground level of ancient cities tended to steadily rise. Settlements constantly imported food and building materials for the population, but getting rid of waste and rubbish was a much lower priority. New houses were built on top of the ruins of old ones because hauling away rubble was labour intensive and it was much easier to simply spread it out and build straight on top.

Rivers periodically flooded and added a layer of silt, while in dry regions the wind was constantly blowing in sand and dust. (The Sphinx was buried up to its head in sand until archaeologists re-excavated it in 1817.)

When ancient towns were abandoned entirely, plant seeds quickly took root and created more bulk from the CO2 they pulled from the air. Their roots stabilised the soil created from rotting plant matter and the layers gradually built up.

Read more: