This week marks 100 days since the World Health Organisation (WHO) received the first report of an unknown illness affecting a number of people falling ill in Wuhan, China.

Coronavirus has since claimed tens of thousands of lives across the world and been labelled a pandemic by the WHO.

But how far have we come since December 31 last year, and what do we know about COVID-19?

What is COVID-19?

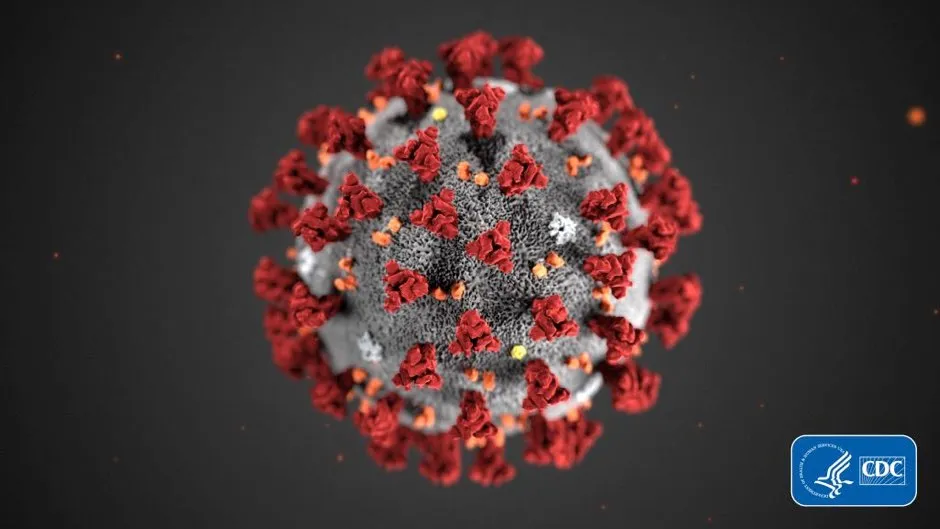

Coronaviruses are a family of viruses that cause illness in humans and animals.

Seven different types have been found in people, including those responsible for COVID-19 and the SARS and MERS epidemics.

Based on early suggestions, it is thought the current virus is more contagious than SARS, with one person infecting around three others.

Coronaviruses cause respiratory and intestinal illnesses in humans and animals.

Where did the coronavirus come from?

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the virus responsible for the current pandemic of coronavirus disease, which was first identified in Wuhan, China, following reports of serious pneumonia.

It is thought the outbreak may have started in Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, which sold live animals.

COVID-19 is believed to have a zoonotic origin, meaning it was active in animals before it was transmitted to humans.

Unconfirmed reports have suggested it could have originated in bats or pangolins.

Are there any treatments or vaccinations for coronavirus?

There is no specific treatment or vaccine for coronavirus, and researchers across the world are racing to develop both.

Experts seem to be in consensus that a vaccine is the ultimate exit strategy from the disease.

It is hoped a vaccine may be given emergency approval before the end of the year, but most scientists agree that it will be around 12 months before one is widely available for use.

Read the latest coronavirus vaccine news:

- Fingertip-sized coronavirus vaccine 'ready in months'

- Coronavirus antibody tests: How they work and when we'll have them

- How are scientists developing a coronavirus vaccine?

- Coronavirus vaccine: first volunteers receive trial dose in US

When will the pandemic end?

While there are signs of the infection rates dropping in some countries like China, this follows months of lockdown that restricted people’s movement.

There are a limited number of ways out of the crisis – vaccination, enough people developing immunity through infection, or permanently changing the way we live to keep some of the measures that have been introduced in place.

A vaccine may be 12-18 months away, and it may take years for herd immunity to develop – where so many people have already been infected with COVID-19 that the virus struggles to spread.

While the UK Government insists this is not a policy aim, over time it may just become a reality.

Can I get the coronavirus twice?

There have been a few stories in the press of people apparently being re-infected by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. These people reportedly became infected and hospitalised, and then were sent home once they’d tested negative for the virus. Then, days or weeks later, they tested positive again.

But this doesn’t necessarily mean that they caught the coronavirus twice.

First, during recovery from infection, a person may have very low amounts of the virus remaining in their body – low enough that our tests can’t accurately detect it. In this case, the person may be sent home on the assumption that they’re virus-free. However, their body may still be fighting the virus, and a resurgence of the virus (and symptoms) can occur, resulting in a positive test. In this case, it would just be one protracted infection, not a re-infection.

Read more:

- How do scientists develop vaccines for new viruses?

- Can I get the coronavirus from a parcel?

- How do viruses make us ill?

- Can my dog get coronavirus?

Second, we know that in most people, SARS-CoV-2 generates a strong response from the immune system. With the related coronavirus SARS-CoV, this response creates an immune memory of the virus that prevents re-infection for one to two years, and it’s likely that this is also the case for the new virus. SARS-CoV-2 also has a fairly low mutation rate, which means that it (hopefully) won’t change enough that our immune system no longer remembers it (this is what the flu virus does and why we need a new jab every year).

If this all turns out to be true, then it would suggest that re-infections are unlikely and that the cases in the news reflect testing sensitivity. However, SARS-CoV-2 is so new that we won’t know for sure until we’ve found out just how protective our immune response to the virus is, and how long it lasts.

Read more about how to survive the coronavirus pandemic:

- Corrupted Blood: what the virus that took down World of Warcraft can tell us about coronavirus

- Coronavirus: Will COVID-19 become a seasonal virus?

- How to cope with anxiety and take care of your mental health during the coronavirus pandemic [via Calm Moment]

- Big tech and coronavirus: How Google and Facebook could take on the pandemic

- What nature can teach us about friendship in the time of coronavirus

- Stash-busters! 30 easy arts and crafts to do at home [via Gathered]

- 10 science-backed tips to help you work from home successfully

- 15 super fun DIY science experiments for kids to try at home

- Astronomy in isolation: stargazing activities for those stuck at home [via Sky at Night Magazine]