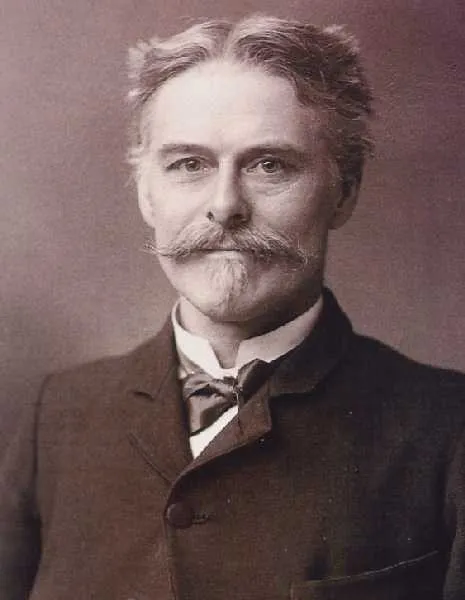

Every science has its celebrities. Physics has Einstein. Chemistry has Marie Curie. Evolution, Charles Darwin. And in palaeontology, it’s two men who so thoroughly despised each other that they’d certainly be rankled by the fact that you can’t mention the name of one without the other — Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope.

The everlasting enmity between the two fossil hunters took time to develop. In fact, they started as friends. Both were young American scientists determined to be the late nineteenth century’s paleontological pioneers.

The discipline had not yet put down academic roots in the United States, and the two met while trying to glean what they could from the German authorities on the subject before establishing themselves in East Coast academic circles.

They left behind almost no record of these early encounters — among the few amicable ones in their careers — but they got on well enough that, in 1868, Cope invited Marsh to visit one of the southern New Jersey marl pits that were keeping him well supplied with prehistoric fossils.

It was a sweet arrangement. The greensand was loaded with a mineral called glauconite, often used as a fertiliser, and the miners working the site regularly ran into the remains of creatures that had lived along the New Jersey coast more than sixty-six million years ago. Some, such as turtles and crocodiles, were vaguely familiar, but there were also tidbits of dinosaur and the fossils of gigantic seagoing lizards called mosasaurs.

Read more about bones:

- Journey underneath the skin with these amazing pictures from the new book Anatomicum

- Are human and animal bones the same?

Even better for a naturalist with entire fossilised worlds waiting to be analysed and described, the affluent Cope didn’t have to dig through the muck himself. All he had to do was pay the miners for the better selection of specimens they encountered as they scraped the pits.

Marsh — an ambitious man from a rich family that included his philanthropic uncle, George Peabody, who founded a museum at Yale for his nephew in 1866 — could easily afford to do the same. When he saw the scientific potential of the fossils coming from Cope’s connections, Marsh paid off the miners to send the bones north to his collection in New Haven rather than west to Cope’s study in Philadelphia.

This was the paleontological equivalent of the shot heard round the world. Cope was furious that he had been undermined by Marsh, and this insult was just the first of many they’d exchange over the years.

Their brilliance and arrogance made them the most cantankerous of adversaries. They practically dragged the entire field of palaeontology into their squabble as they rushed to telegraph in species descriptions from western outposts and used their personal fortunes to fuel their fierce publication rate, always desperate to outdo each other.

The effects weren’t all bad. The world was introduced to Mesozoic celebrities such as Triceratops, Brontosaurus, and Ceratosaurus as a result of this competition, which also changed the nature of the field.

Not only were Cope and Marsh some of the first palaeontologists to develop expertise in a wide variety of animals — describing fish, reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals as they pleased instead of focusing on one group — they also hired and trained those who would become the next generation of American palaeontologists.

Still, both Cope and Marsh were capable of holding a grudge with such endurance that in 1873 the editors of the scientific journal The American Naturalist — which Cope himself had purchased as a personal publishing platform — eventually refused to accept any more papers feeding the contest, informing readers that “the controversy between the authors in question has come to be a personal one and [because] the Naturalist is not called upon to devote further space to its consideration, the continuance of the subject will be allowed only in the form of an appendix at the expense of the author.”

That did nothing to quell the clash between the scientists. In 1890 the New York Herald brought the conflict public under the headline 'Scientists Wage Bitter Warfare', making other palaeontologists feel like their entire profession had been publicly tarred.

In the end, both men lost.

Decades of trying to outdo each other had winnowed their personal finances to nearly nothing, and the stress had wracked their bodies. In 1897 as Cope lay dying in his personal museum, surrounded by his fossils and reptilian pets, he wasn’t about to admit defeat to Marsh. Cope had plans to carry the Bone Wars into the afterlife.

Read more about great scientists:

- Peter van de Kamp: the astronomer who was wrong in all the right ways

- Ada Lovelace: a mathematician, a computer scientist and a visionary

No one knows exactly what killed Cope. There is no evidence to support the rumours that he succumbed to syphilis from a dalliance earlier in his life. He suffered for years from chronic infections and problems with his bladder, prostate, and neighbouring tissues, for which he mostly medicated himself.

Despite the urging of his friends, surgery to relieve some of his pains was out of the question. Such procedures were still in their infancy, historian Jane P. Davidson wrote in her biography of the scientist, and the prospect of accidentally being rendered impotent was one that Cope wasn’t able to endure.

He just continued to take belladonna — a poisonous plant that may have contributed to his death — and write up scientific papers when he could, locked in competition with Marsh until his final days. And he had a plan. Before he died on 12 April, 1897, Cope set out a biological challenge for his Yale rival that would settle the question of who was the greatest palaeontologist once and for all.

Cope did not care much for the bulk of his flesh. His muscles and nearly all of his vital organs were burnt to ash and placed in Philadelphia’s Wistar Institute. But he had other wishes for the rest of his remains.

“I direct that after my funeral my body shall be presented to the Anthropometric Society and that an autopsy shall be performed on it,” Cope wrote in his will, stipulating that “My brain shall be preserved in their collection of brains” for future study. This was his final act of throwing down the gauntlet. He had given his brain to science to be weighed and measured, confident that the grey matter between his ears would outweigh that of Marsh.

But Cope’s nemesis never took the bait. Electing a burial less primitive than the fossils he loved, in 1899 Marsh was interred in a cemetery not far from the museum he had given his life to.

The Secret Life of Bones: Their Origins, Evolution and Fate is out now (£9.99, Duckworth).