Reaching dizzying speeds of up to 200 miles per hour, the peregrine falcon is the fastest member of the animal kingdom by far. But with its vast wingspan and sophisticated aerodynamics, the peregrine has everything going for it.

It’s time to appreciate some of the more impressive feats of flight, from some surprising flying animals that really shouldn’t take to the skies.

1

Flying fish

Apparently life in the sea just isn’t cutting it for our finned friends anymore, with some fish venturing out of the water and into the skies.

Flying fish are members of the family Exocoetidae, and use their remarkable abilities to shake off predators. Whilst underwater, flying fish make good use of their super-streamlined shape to gain speeds of up to 60 kilometres per hour, placing them in thetop 10 fastest fish. They then propel themselves upwards to break the surface, where they use their tails to skim along the water before fully taking to the air.

Their impressive pectoral fins help them reach heights of 1.2 metres and distances of up to 200 metres. But that’s not all - when the fish lose height and approach the water, they can again beat their tails to travel across the surface and prolong their flight to 400m!

Read more:

- Eight of nature’s grooviest dancing animals

- Dude, where’s my flying car? 11 future technologies we’re still waiting for

2

Japanese flying squid

It’s probably not what you want to hear, but yes, some squid can fly. In fact, several squid species have been reported to be able to launch themselves out of the water, but only one has been properly studied and its abilities fully described.

Unusually, the squid from the family Ommastrephidae uses jet propulsion to drive itself into the air, by drawing water underneath its mantle – its outer layer – and releasing it in a high-powered blast. Its fins and tentacles then double as wings, creating aerodynamic lift, which allows it to travel for three seconds and cover distances of 30 metres.

This fine-tuned technique, in which the squid carefully adjusts its posture to prolong its flight, has prompted scientists to declare that the squid it not simply gliding, but truly flying.

Most impressively, this unassuming squid could give Usain Bolta run for his money, reaching speeds of 11.2 metres per second, compared to Bolt who averaged 10.5 metres per second in his 2009 100 metre world record sprint. Now that really is the stuff of nightmares.

3

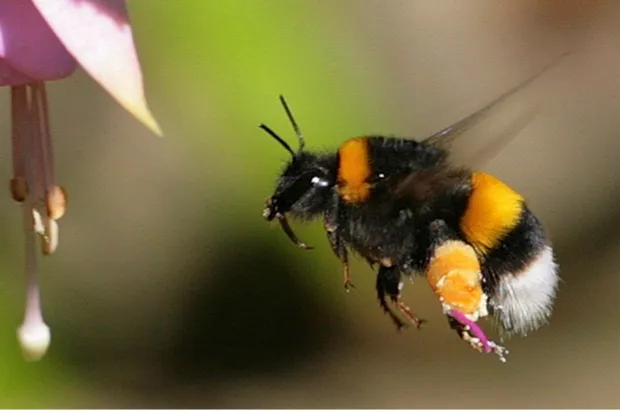

Bumblebees

Businesswoman Mary Kay Ash helped spread the popular myth that the bumblebee defies the laws of aerodynamics when she said “aerodynamically, the bumblebee shouldn't be able to fly, but the bumble bee doesn't know it so it goes on flying anyway”.

Obviously, there’s no question as to whether bumbles can fly, since we see bees flying all the time. Rather, it was our own calculations that were wrong, being based on the early aerodynamic theory of 1918-19.

These calculations suggested that the bumblebee’s tiny wings could not produce enough lift to get it off the ground, but failed to recognise that a bee does not flap its wings up and down, but back and forth. This movement creates mini hurricanes, which in turn generates areas of low pressure above the wing and, voila, the bumblebee can fly!

The bee still has incredibly poor aerodynamics (perhaps that’s not surprising, looking at its chunky physique) but the tough little insect overcomes this by using good old brute force to pull itself through the air. With this in mind, what’s probably more surprising is that bumblebees are actuallyrather adept at football.

4

Hummingbird

A bird might seem out of place on a list of things that shouldn’t fly, but if you’ve ever studied a hummingbird in flight, you’ll know it’s quite special.

Backwards, sideways, hovering, somersaults - this tiny bird can move in ways that others can only dream of, and it does it by inverting its wings to produce lift on the upstroke as well as the downstroke.

This technique is actually more similar to that of an insect than the hummingbird’s avian kin, but the hummingbird’s skeleton does not allow it to rotate its wings at the base like an insect, so instead it twists its wrists.

5

Mobula rays

Yet another sea dweller that fancied a change, these rays areclosely related to sharks but are perfectly designed for flying through the air. With slender bodies and wing-like pectoral fins, they can reach heights of over two metres, before returning to the water with a loud smack.

Hundreds of mobula rays congregate together to put on a performance that has been likened to watching a pot of popcorn, due to the sight of them exploding into the sky, followed by the chorus of popping sounds as they strike the surface. As yet, scientists are unsure why the rays put on such a spectacle, but it is most likely a form of communication to attract a mate.

6

Puffins

Puffins might not look like the most adept flyers, but they’re niftier than you might think. Beating its little wings at 400 beats per minute, so fast they appear a blur, a puffin can reach speeds of 55 miles per hour.

But in a curious twist, the puffin can also explore the marine world byflying underwater. The puffin partly folds its wings and angles them backwards, and using its speedy flapping, it dives to a depth of up to 60 metres, remaining underwater for 30 seconds.

This brilliant tactic means the puffin is still flying, only meeting a little more resistance than in air, and is so sophisticated that it has inspired somepretty cool tech.

7

Humans

It probably hasn’t escaped your notice, but human beings aren’t exactly designed for flight, yet we have rebelled against our terrible aerodynamics and left the ground anyway.

We have been creative in our journey to aviation too, fashioning wingsuits,balloons,helicopters, gliders, andaeroplanes. Looking at our handiwork though, it’s sometimes amazing that our bulky metal machines can stay airborne. They truly are impressive feats of engineering, but what’s even more extraordinary is that we’re ditching as much of this metal as possible, with adventurers such as Yves Rossy effectively strapping a rocket to his back and taking to the skies.

For the rest of us though it’s just better to close your eyes and hope that the laws of physics don’t suddenly realise that we’ve defied them.