More than 400 new species previously unknown to science have been discovered in the past year by experts at the Natural History Museum.

Species described and named for the first time in 2019 include 171 beetles found around the world, one of which was named in honour of teenage environmental activist Greta Thunberg.

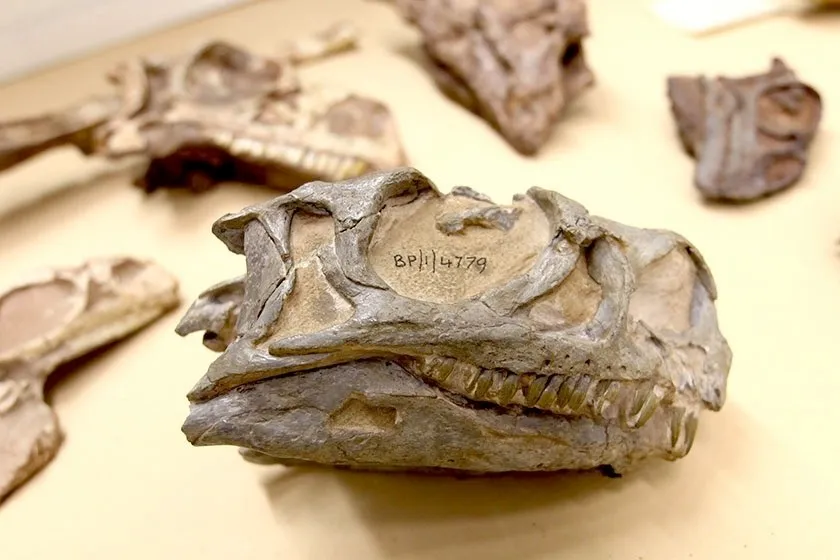

New finds of lichen, marsupials, snakes and even long-extinct dinosaurs are among the 412 species officially named in the past year by the museum’s scientists, who represent one of the world’s biggest groups working on natural diversity.

But the experts warn that species are being lost faster than they are being discovered and many may be vanishing before they are even known about.

Read more about new species:

- 9 animals named after rock bands

- Idris Elba "honoured" to have new species of broccoli parasite named after him

- There’s always a bigger fish: Animals named after Star Wars creatures and characters

The museum’s executive director of science, Tim Littlewood, said: “Species discovery is always exciting and shows just how much there is still to understand about our planet.

“Learning how evolution has yielded new species able to live in Earth’s diverse habitats is awe-inspiring.

“Sadly, much of that adaptation and biological diversity is now severely threatened and we are losing species faster than we can discover them.

“We are losing our understanding of the natural world, breaking our own connection with it and the connections that underpin nature’s stability.”

The largest group of newly described species are Coleoptera, or beetles, found in places including Japan, Malaysia, Kenya and Venezuela, with scientific associate Dr Michael Darby naming the Nelloptodes gretae after 16-year-old Swedish schoolgirl Greta.

Max Barclay, senior curator in charge of Coleoptera at the Natural History Museum, said: “The name of this beetle is particularly poignant since it is likely that undiscovered species are being lost all the time, before scientists have even named them, because of biodiversity loss.

“So it is appropriate to name one of the newest discoveries after someone who has worked so hard to champion the natural world and protect vulnerable species.”

This year has seen the naming of eight lizards, five snakes, four fish and an amphibian native to India, including Trimeresurus arunachalensis, the first new species of pit viper described from the country in the last 70 years, as well as new wasps, centipedes, aphids, snails, moths and butterflies.

Discoveries of extinct species including the pig-footed bandicoot Chaeropus yirratji, an unusual marsupial that had vanished by the 1950s.

And two new species of dinosaur were discovered, including a stegosaur Adratiklit boulahfa, found in Morocco.

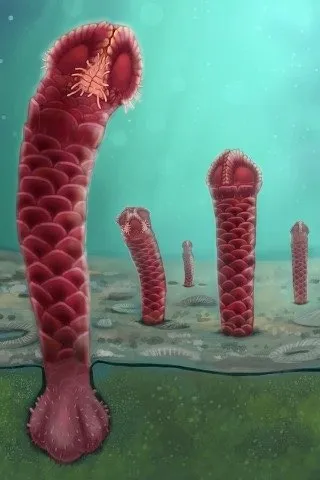

The 2019 discoveries also included seven new plants and seven lichen, as well as 12 species of deep sea polychaete worms from the sediments of the dark depths of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean.

Reader Q&A: What is the minimum difference a species must show in order to be classed as a new species?

Asked by: Adam King, Huddersfield

This is less straightforward than it seems. The concept of species, as a way of classifying animals and plants, relies on finding some trait that all members of that species share, and which is unique to them. This works pretty well for many organisms, but species are continually being lumped together or split into two as biologists search for the perfect classification system.

There are currently at least 26 different ways to define the concept of a species. Some consider physical or genetic similarity, while others consider whether populations interbreed – or whether they could if they weren’t separated by a geographical barrier, such as a mountain range or ocean. Other definitions of species focus on the evolutionary history of the organism, grouping species according to how recently they shared a common ancestor.

Even if biologists could agree on a single definition of a species, identifying a point at which a new species is created would still be difficult. Theoretically, the minimum difference could be a single mutated gene, marking a fork in the evolutionary tree where one species splits into two.

However, biologists almost certainly wouldn’t recognise the creation of the new species until later, when the genetic mutation manifested as a difference in the way the animal looked or behaved.

The closest we’ve come to this was probably in 2016, when researchers at the Janelia Research Campus in Virginia artificially altered the genome of a species of Drosophila fruit fly. This change to a single gene altered the frequency of the courtship ‘song’ produced by the male fly.

The insects that carried this gene could still mate with the wild population, so they couldn’t be considered a separate species by most definitions. But they preferred to mate with similarly mutated flies, and if this mutation had occurred in the wild, it’s possible that this might have resulted in the evolution of a new species.

Read more: