What’s your favourite animal? If you know anything about them, your answer is likely the mantis shrimp.

From their deadly 23m/s punch, to their unique photoreceptors and secret communication channels, here’s everything you need to know about these amazing creatures and stars of BBC’s Life in Colour.

How many colours can mantis shrimp see?

It’s difficult to answer as mantis Shrimp see the world so differently to us.

That’s because while our eyes only have three photoreceptors – and most mammals have two – mantis shrimp have 12.

“They have probably the most complex vision of any animal we've looked at so far. It's just astonishing and mind-blowingly complex,” says Dr Martin How from the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Bristol, who worked in an advisory role on Life in Colour.

“They can see many colours with their independently-moving eyes. Plus, they have ultraviolet sensors and they have polarisation vision.”

Read more about the science of light:

- Why does light travel faster than sound?

- Why does light leave the position from which it is created?

- Do two mirrors facing each other produce infinite reflections?

So, what is polarised light? “Basically, light is a wave. And because it’s a wave, it also has a direction. The light can go up and down, or side-to-side at any angle. Polarised light is when these waves all move in the same direction.”

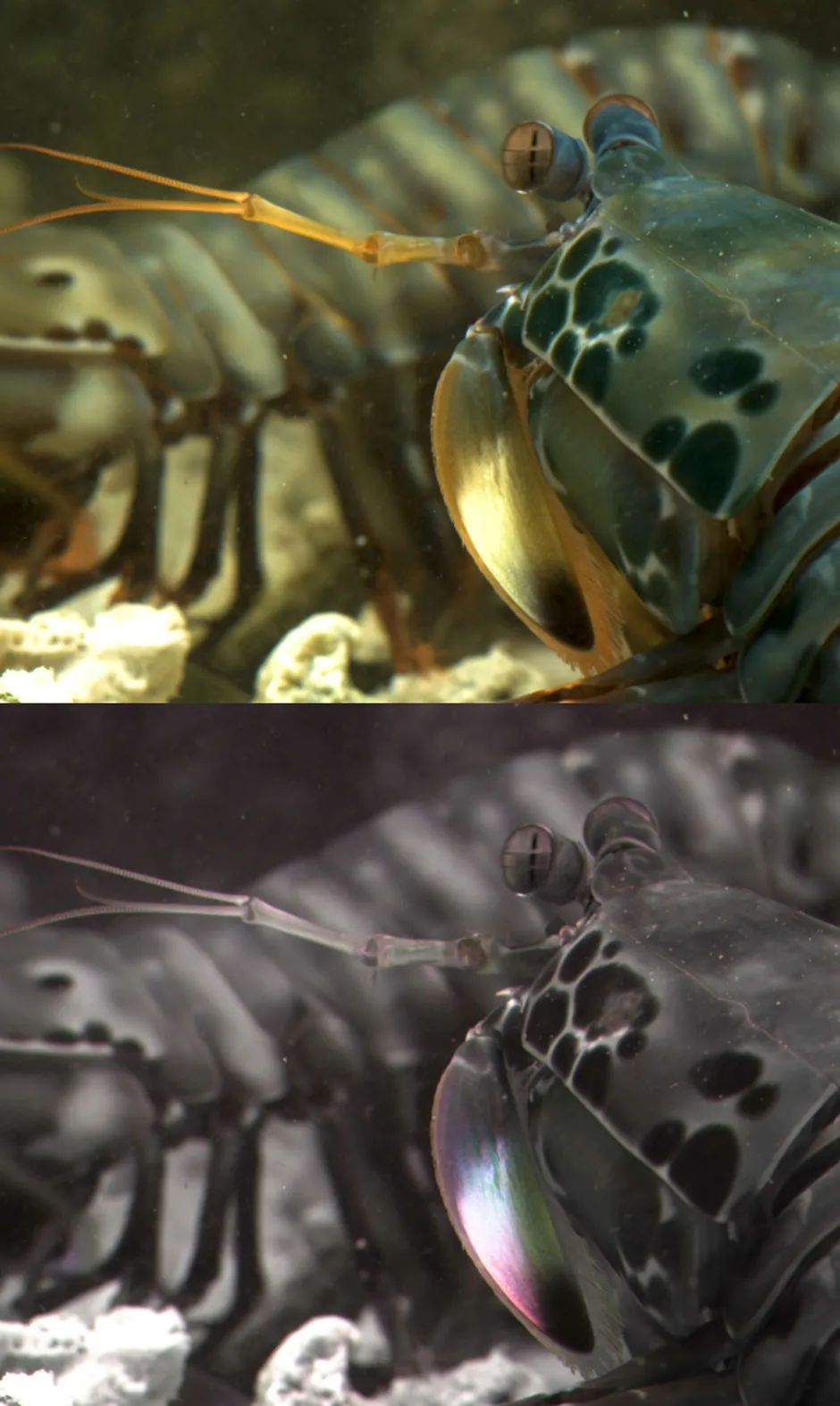

Because not a lot of animals – including us – can see in this way, mantis shrimp use this to their advantage, reflecting polarised light with their bodies to communicate with one another.

“The messages themselves aren’t too complex. They could simply be indicating ‘I’m a really scary male, don’t come near me.’ But the amazing thing here is that mantis shrimp can be totally camouflaged to other animals, yet clearly visible to each other,” says How.

However, as How learned during experiments, mantis shrimp aren’t particularly good at differentiating colours.

“It’s because the way they see colour is very different to our own,” he explains.

“So, humans compare the information from our three colour receptors, seeing red, green, and blue and all the colours in between those three peaks. However, we think mantis shrimp just see 12 colours. They almost have a barcode scanner for colour rather than a hue detector.

“It’s extremely hard to get into the mind of the mantis shrimp, but we think they deal with this by segmenting their vision – using their different sense of colour at different opportunities, such as checking out prey before striking.”

How powerful is a mantis shrimp punch?

Why was Sylvester Stallone and not a mantis shrimp the star of Rocky? Apart from lacking in screen acting experience, the mantis shrimp would never be the underdog in a boxing match.

This is because many mantis shrimp wield club-like calcified appendages that use elastic forces to smash enemies with tremendous speed – roughly 80km/h, accelerating at up to 10,000 times the force of gravity.

It’s so quick and creates so much pressure, that the shrimp actually vaporises the water in front of it. This creates small ‘cavitation bubbles’ that not only emit bright light, but also temperatures of around 4,000°C.

“The force of the punch combined with these bubbles really is a double whammy to any opponent,” explains How.

The good news: if you’re in a fight with a mantis shrimp, not all 500 species have such a club. The bad: they could well have a spear instead.

“Species of mantis shrimp that need a long reach have these,” says How. “When hunting, they sit in a burrow and will launch themselves out when a fish swims by and spear them. It’s a truly amazing sight.”

Is it true that mantis shrimp are not actually shrimp?

Indeed, the mantis shrimp is not a shrimp. Or a mantis.

“They’re actually their own group of animals called stomatopods – a totally separate group of crustaceans,” says How.

“These creatures are 400 million years old – that’s older than the dinosaurs – they have their own very special evolutionary root. It’s why they’re so successful – and incredible.”