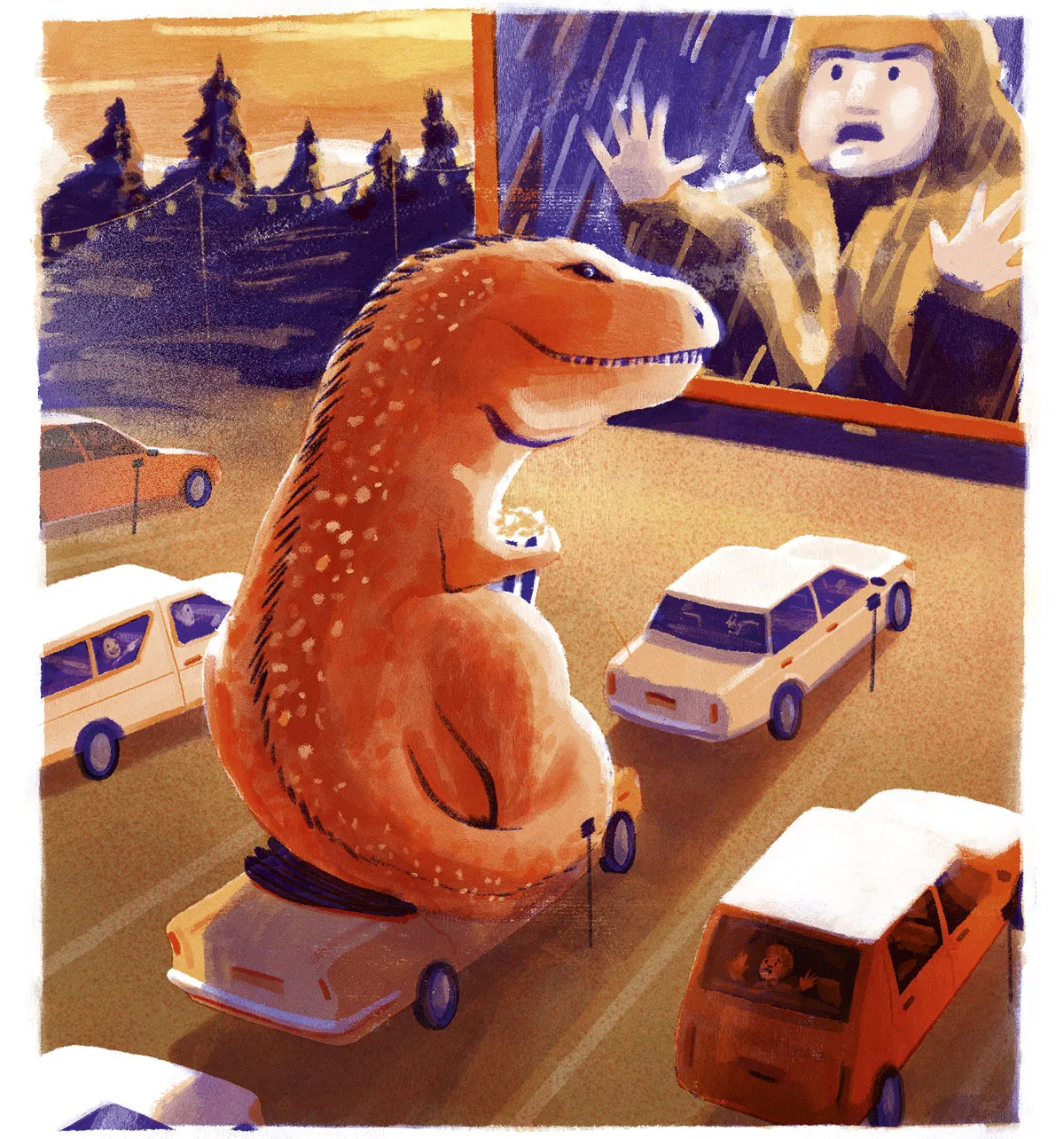

The new Jurassic World movie envisions a time where dinosaurs are no longer every theme park’s health and safety nightmare, but have instead started to reintegrate themselves as an ordinary part of our modern wildlife. Velociraptors stalk the woods like wolves. Men on horseback herd Parasaurolophus like cattle. A Tyrannosaurus rex disrupts a drive-in movie like… a bloody massive Tyrannosaurus rex.

It’s a premise that raises interesting questions. What impact would reintroducing dinosaurs into the wild have on our ecosystem, for example? And how would dinosaurs fare in a world so profoundly different to the one they originally lived in?

Prof Steve Brusatte, a palaeontologist at the University of Edinburgh and an advisor on Jurassic World Dominion, theorises that introducing, say, a T. rex into the British countryside would not be a great idea.

“There have been many cases where a predator is introduced to an ecosystem and wreaks havoc,” he says. “It’s happened when we brought rats or dogs to new islands, so just imagine something at the T. rex’s scale. It could certainly lead to some mammals going extinct.”

It’s not only carnivores that would disrupt the ecosystem, however. Giant herbivores like Brontosaurus could have a profound effect on crops and other plants that are important medicinally, says Brusatte. “Even the most conservative estimates say that sauropods would have eaten hundreds of pounds of leaves and stems every day.”

But there is a question of whether dinosaurs could even survive long enough in our modern world to have any lasting impact at all. “Dinosaurs like Brontosaurus, Diplodocus and Brachiosaurus lived in the Jurassic,” says Brusatte. “There were no fruits or flowers. Flowering plants were not even around until the early part of the Cretaceous.

"The vast majority of dinosaurs would never have seen a flower. Their diets were based on totally different types of plants. So whether they could even eat most of the food available to them today would be a really big question.”

And then there’s our climate. There is much debate over whether dinosaurs were primarily cold-blooded or warm-blooded, with recent studies (and Brusatte) concluding that they were likely a mix of both. Either way, the answer would have a huge effect on how easily dinosaurs could adapt to our environment.

“The global baseline for the temperature was much higher during the time of the dinosaurs,” says Brusatte. “If they were fully warm-blooded, they could probably live in the kind of places that a lot of mammals could today. If they were more cold-blooded, that’s different. We don’t have crocodiles here in the UK for a reason. So if the dinosaurs did have more of a cold-blooded physiology, that’s big swaths of the world today where they couldn’t live.”

However, Brusatte is optimistic that dinosaurs could adapt to whatever the natural world throws at them – apart from an asteroid. Instead, he suggests that their biggest danger would be co-existing with the apex predator of humanity.

“I think, in reality, we would just kill all the dinosaurs,” he says. “I mean, if some mad scientist suddenly announced, ‘hey, I’ve cloned 10,000 T. rex and they’ve all escaped,’ the first thing we would do is hunt them down. Maybe we would co-exist with Triceratops or Brontosaurus, but big predatory dinosaurs? We have such deadly weapons and are really good at killing off things – I don’t think we would co-exist.”

Life, it turns out, would not find a way.

Verdict:Much as we might like to live alongside some dinosaurbuddies, our aptitude for destroying wildlife and the world means it’s probably not possible.

About our expert, Prof Steve Brusatte

Prof Steve Brusatte is a vertebrate palaeontologist and evolutionary biologist who specialises in the anatomy, genealogy, and evolution of dinosaurs and other fossil organisms. He has written over 110 scientific papers, published six books (including the adult popular science book The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs, the textbook Dinosaur Paleobiology, and the coffee table book Dinosaurs), and has described over 15 new species of fossil animals.

Read more fromPopcorn Science: