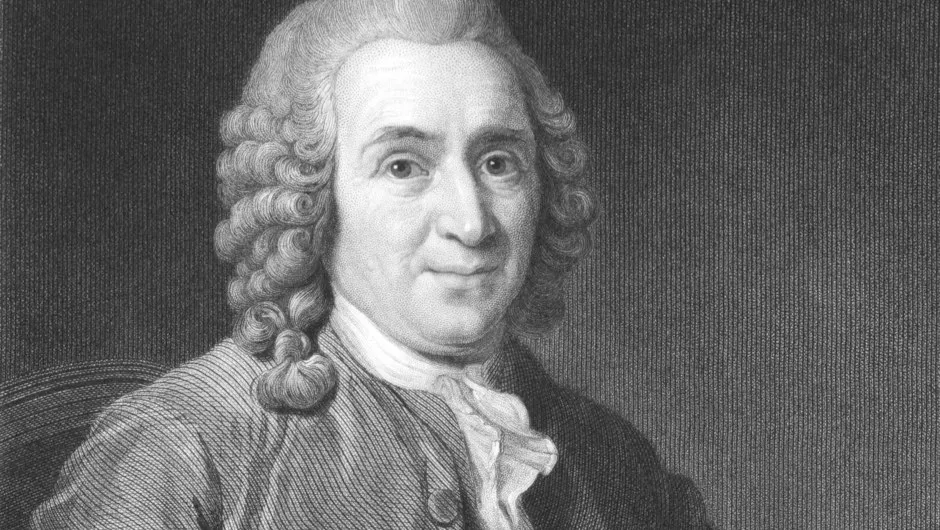

When Carl Linnaeus invented modern “binomial” Latin names, he made it possible for a scientist naming a new species to honour someone admirable or notable. But any tool that can build can also tear down; and just as Latin names can honour, they can dishonour.

Linnaeus was the first to use naming to celebrate scientists who had gone before him—but he was also the first to succumb to temptation, and use Latin naming to insult someone with whom he had quarrelled. He wouldn’t be the last.

Linnaeus’s most famous work, the Systema Naturae, used a new system for classifying plants: his “sexual system,” in which plants were assigned to classes and orders based entirely on the number and arrangement of stamens and pistils in their flowers (stamens are the male, pollen-bearing structures, and pistils the female, ovule-bearing structures).

For instance, his grouping “Octandria Monogynia” included plants with eight stamens and one pistil (“Octandria” from the Greek octo = eight, and andros = man, and “Monogynia” from the Greek mono = one, and gyne = woman). In places, Linneaus used somewhat bold language about this. For example, he described the Octandria Monogynia as “Eight men in the same bride’s chamber, with one woman,” and he explicitly equated the stigma to the vulva and the style to the vagina.

Read more about new species:

- There’s always a bigger fish: Animals named after Star Wars creatures and characters

- Nine animals named after rock bands

- Fish with Black Panther-inspired name one of 71 new species found in 2019

- Members of new crocodile species identified in zoo

He even waxed eloquently (and erotically, for the time) about how “petals do service as bridal beds . . . adorned with such noble bed curtains and perfumed with so many soft scents that the bridegroom with his bride might there celebrate their nuptials .... When now the bed is so prepared, it is time for the bridegroom to embrace his beloved bride and offer her his gifts.”

This sexual frankness didn’t sit well with some of his contemporaries. A Prussian botanist named Johann Siegesbeck was particularly scandalised, condemning Linnaeus’s system in a 1737 book as “lewd” and objecting to the notion that flowers could commit such “loathsome harlotry”—among other choice words.

Siegesbeck and Linnaeus had previously enjoyed a friendly correspondence, but Linnaeus didn’t take criticism well. He retaliated by naming a new species, Sigesbeckia orientalis, after Siegesbeck.

How was this “retaliation”? Sigesbeckia is a small, unpleasantly sticky and rather unattractive weed, and one with tiny flowers to boot. Given Linnaeus’s explicit association between plant and human sexual organs, his choice of a tiny-flowered species was surely no accident.

In fact, the whole thing was far from subtle: earlier in the same year, Linnaeus had published his Critica Botanica, in which he set out explicitly the principles by which Latin names were to be constructed. Among these was that there should be a clear link, and preferably a resemblance, between the plant and the botanist it was named for.

With this on record, it was impossible to miss the intended insult in Sigesbeckia. Or at least, impossible to miss it for long. Siegesbeck first thanked Linnaeus in a letter for having honoured him with Sigesbeckia—but at that point, he was unfamiliar with the plant in question. Later, he came to understand, and Siegesbeck and Linnaeus would be enemies for the rest of their lives.

Linnaeus’s sexual system didn’t prove particularly useful as a way of classifying plants. Plant sexual anatomy is important, but just counting stamens and pistils doesn’t get you very far.

Before long, the sexual system was largely abandoned—even by Linnaeus. It was replaced by various other systems that integrated information from many different traits in an attempt to organise plant diversity more naturally (and eventually, evolutionarily).

Siegesbeck’s objections, then, have become moot; but we still use the name Sigesbeckia, and Sigesbeckia orientalis is still weedy, sticky, and unattractive.

Read more book extracts:

- Zoology in 30 seconds: conservation and extinction

- The Bone Wars: how a bitter rivalry drove progress in palaeontology

- Why we need to rethink the way we classify people

Linnaeus didn’t actually come right out and say that he meant Sigesbeckia as an insult (although it was pretty hard to miss). He was a bit more up front (in Critica Botanica, his work from 1737) with a handful of other namings.

Among them: Pisonia, a thorny and “sinister” tree for Willem Piso, whose work on Brazilian botany was sometimes held to be derivative of the earlier Georg Marcgraf; Hernandia, a tree with handsome leaves but inconspicuous flowers, for Francisco Hernández, whose work Linnnaeus judged ultimately unproductive; and Dorstenia, a group of mostly herbaceous relatives of mulberries, “whose flowers are not showy, as though they were faded and past their prime, [which] recalls the work of [Theodor] Dorsten.”

Piso, Hernández, and Dorsten were all long dead when Linnaeus used naming to make his feelings clear, though. Only Siegesbeck was alive to feel the sting.

Charles Darwin’s Barnacle and David Bowie’s Spider: How Scientific Names Celebrate Adventurers, Heroes, and Even a Few Scoundrels by Stephen B. Heard is out now (£20, Yale University Press)