We are lucky enough to hear the chirps, whistles and songs of numerous bird species throughout the year in this country, but a unique fossil found on Vega Island, Antarctica, suggests that birdsong could also be heard more than 66 million years ago, albeit likely a less whimsical honking sound.

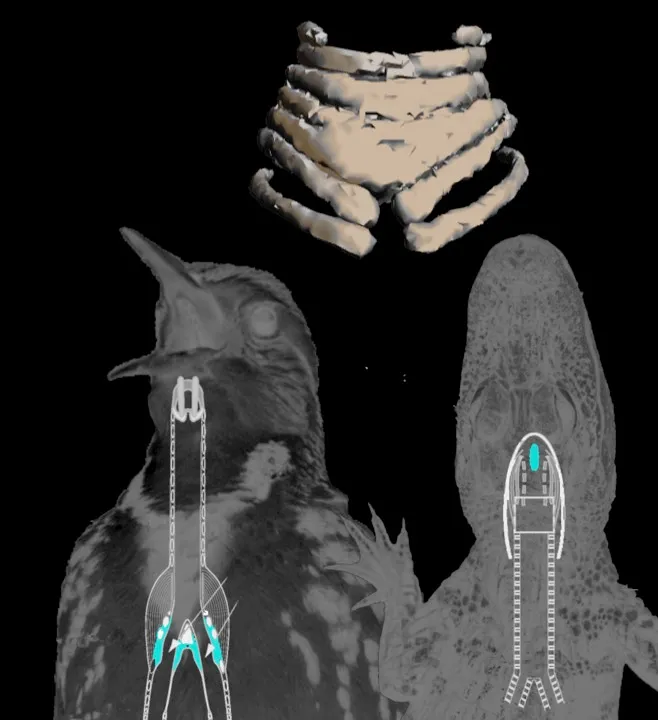

Vegavis iaai, an ancient bird described as close relative to ducks and geese would have lived at the same time as Tyrannosaurus rex, and was first discovered in 1992. But the presence of an avian voice organ, the syrinx, only recently noticed, gives an important insight into what the animal sounded like, which a new study, published in Nature, suggests made it sound similar to modern birds.

The syrinx itself is made from soft tissue supported by cartilage rings, which in most cases do not undergo fossilisation, but the mineral content in cartilage, although not as high as bones, sometimes allows for it to happen. What makes this discovery particularly special is that previous fossilised syrinx discoveries came from birds that lived well after non-avian dinosaurs went extinct, making this specimen the oldest to date.

“This finding helps explain why no such organ has been preserved in a non-bird dinosaur or crocodile relative,” says Julia Clarke, palaeontologist at the University of Texas, who discovered the syrinx and led the analysis. “This is another important step to figuring out what dinosaurs sounded like as well as giving us insight into the evolution of birds.”

The asymmetrical nature of the discovered syrinx when compared to those of modern birds suggests that a honking sound would have been produced from two separate sources from each side of the organ. This honking would have been in stark contrast to the noise dinosaurs without a syrinx would have made, which Clarke suggests in an earlier studywould have been made with closed mouths, sounding similar to the boom of an ostrich.

The research team is now working with engineers to produce replication models.

“This is an incredible fossil discovery,” Dr Stephen Brusatte, palaeontologist from University of Edinburgh, tells us in an email. “It tells us that these early birds living alongside the dinosaurs may have sounded like some of the birds around today. The Late Cretaceous air may have been filled with the songs, chirps, and honks of birds!”

As with many species, including ourselves, the evolution of vocal communication is not just a significant milestone in itself. Further insight can tell us much more about both birds and dinosaurs, such as the when the appearance of larger and more complex brains occurred in birds.

“Birds evolved from dinosaurs, but since we don't have any vocal boxes preserved until very advanced birds like the Vegavis fossil, it seems like dinosaurs couldn't produce the same sounds as birds.” says Brusatte. “The ability to make those sounds evolved with the vocal box, much later in evolution.”

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard