Butterflies are seemingly fragile insects, fluttering off in fear if you interrupt their flower feast. Yet, from their outstanding vision, to their less-than-delicate beginnings, there's a lot of science to unravel.

Even the colourful patterns and beat of butterfly wings are more than what meets the eye. Read on for everything we know about these bewildering creatures and how the science of butterflies has contributed to innovations in technology.

How long does it take for a caterpillar to turn into a butterfly?

We’ve all heard the story of The Very Hungry Caterpillar, who keeps eating and eating as it grows until it eventually transforms into a butterfly.But what’s the science behind the story and how long does it take to form a butterfly?

Like a Charmeleon-to-Charizard evolution in Pokémon, the caterpillar is an early form in the butterfly’s life. While living the sweet life of leaves and leisure, a caterpillar, which is the larva of the butterfly, keeps growing until reaches a ‘critical size’.

At this point, a rush of a hormone (ecdysone) is released. This signals to the little fellow it should shed its skin, or moult, over and over.

Though changing while it moults, it remains a caterpillar thanks to another set of hormones which stop it from developing any butterfly-like features. As well as digesting the plants and ants it’s been crunching on, a caterpillar must effectively digest itself before transforming into a butterfly.

This metamorphosis from the caterpillar to butterfly is generally known as the pupa. It’s a time of growth, change and, yes, a pretty gross digestive process (more on that in the next section).

This stage of the insect’s life cycle can last anywhere from a few weeks up to two years. The difference in timeframe depends on the particular species of butterfly.

What happens inside a chrysalis?

A caterpillar's chrysalis is like a hardened sleeping bag, formed from the caterpillar's own body.

To create these shells, caterpillars first anchor themselves onto a leaf or twig using stem-like appendages called ‘cremasters’. Using this, they hang themselves upside down from a branch or leaf in preparation for the transition. Some butterfly caterpillars have special glands in their mouth which releases a sticky silk substance to secure their chrysalis in place.

Once hooked, the caterpillar constructs the protective chrysalis casing from its own body. By shaking off its outer layer of skin again, it can zip itself up inside the sturdy casing.

Inside this tough casing is where the changes get really incredible and even more disgusting. Having had his fill of food outside the chrysalis, our caterpillar friend releases digestive enzymes. These get to work breaking down the tissue and muscle cells into what is best described as caterpillar soup.

Within this soup, some groups of cells outlast others, and not by chance. Before the caterpillar has chewed its way through your vegetable patch, it has already started developing specialised cells.

Remember that set of hormones preventing the caterpillar from changing too much as it sheds its skin? At this point, these hormones have diminished, and a second avalanche of ecdysone helps the specialised cells to flourish. These will go on to build the butterfly, forming its wings, eyes and more as they differentiate and grow.

From what was once our long, plant-devouring land creature, and through this sloshing soup of cells, we eventually arrive at the delicate butterfly with fluttering wings that can span to 27cm.

How does a butterfly get out of its chrysalis?

Another hormone-controlled process, the emergence of a butterfly from its casingis not as simple just flapping its wings and breaking free.

When a butterfly is fully formed, it will release hormones which act to soften the shell and help the butterfly start moving. Often the shell will become transparent, giving us a peek at the newly formed creature inside.

Once the chrysalis is softened, the butterfly can begin to crack it open. It does this by inhaling air and expanding its wings. It can then push through with its legs and crawl out and continue hanging until its wings dry and spread. One hell of a stretch after being curled up inside.

How long do butterflies live?

Although they can be found all over the world, butterflies have a fleeting life. With an average lifetime of around three to four weeks, most butterflies don’t have long to explore.

However, it varies across different species. In 2009, scientists did a large-scale study and found that butterflies' lives span from a few days to almost a year.

Where do butterflies live?

Butterflies can be spotted flapping around in almost any habitat. Scientists have observed butterflies in the Arctic, with some seen exploring the tundra in the 'warmer’ days, between 15 and 18°C. Like rats, the only continent butterflies can’t be found is Antarctica due to its sub-zero climate.

Monarch butterflies have a longer lifespan than most and will take flight from their native USA and Canada habitats to the warmer climate of Mexico for winter. Some migrating monarch butterflies travel over 4800km to reach their warm winter home.

Unlike birds, butterflies don’t nest – but sometimes their caterpillar babies do. Butterflies will find the perfect plant to home their eggs and if enough are laid together, the caterpillars get constructing.

Scientists have seen that when groups of caterpillars hatch on the same plant, they will work together and build a tent around their plant. With their trusty silk, they tie leaves together to create a little caterpillar home. However, it’s the rare butterfly whose caterpillars will pitch camp. Since these special silk glands are needed, you are more likely to find a moth’s caterpillarsbuilding a silky home.

Can metamorphosis happenin space?

In 2009, NASA put butterflies to the test, launching several caterpillars into orbit and tracking how they develop in microgravity. Microgravity creates almost weightless conditions, and yet the team observed metamorphosis of the Monarch and Painted Lady butterflies in space.

With a little difficulty, the butterflies managed to emerge, bumping into the sides of their habitat and struggling to fully expand and dry their wings as quickly as they would here on Earth.

What do butterflies eat?

Technically, nothing. Butterflies can’t eat anything and instead drink all their nutrients.

While the very hungry caterpillar uses its teeth-like structures, called mandibles, to bite and chew plants and ants, butterflies do not have this same advantage.

Not only do wings grow in during metamorphosis, but the entire anatomy shifts around. One such change influences butterflies’ feeding habits hugely.

Butterflies develop an elongated tube which they use to suck liquid nutrients from plants. Like an incredibly long tongue, this forms during metamorphosis where two C-shaped structures are bridged together.

This structure, called a ‘proboscis’, curls and uncurls when needed for butterflies to reach round into the juicy centre of a flower. Flitting from flower to flower, butterflies will use this straw-like structure to drink their nectar.

But surely butterflies can’t get all their nutrients from nectar?

Well, they do say eat your veg before you have dessert. For butterflies, their caterpillars do the most heavy lifting health-wise. If you’ve wondered why the very hungry caterpillar is so hungry, it’s because it stores up nutrients to help the butterfly later in life.

It may seem like a gluttonous insect, but proteins and minerals gained from the caterpillar’s diet of plants and ants are stored for the butterfly. It’s so important for metamorphosis and sustaining the butterflies through to reproduction, that scientists have observed very hangry caterpillars.

This violent behaviour appears to be triggered by food shortages, with caterpillars becoming more aggressive just before metamorphosis.

Thanks to the effort of their crawling caterpillars, butterflies are free to get their sugar-fix of instant energy from nectar. Some butterflies can also be found drinking from wet soil or puddles.

Groups of butterflies refuelling at muddy puddles are called ‘puddle clubs’.Gulping up muddy water helps butterflies regulate their temperature and increases their salt supply, which improves their reproductive success.

Though they can't offer a shoulder to cry on, butterflies have even been seen lapping up the salty tears of turtles.

Read more about insects:

- What is a mad hatterpillar?

- Do bees have knees, and if so – what’s so special about them?

- A partying caterpillar and a bridge made of ants: The winners of the National Insect Week Photo Competition

How do butterflies taste things?

Though they can’t chew and savour their food, butterflies do still taste – with their feet. While all our taste buds are inside our mouth, butterflies have them across their wings, feet, antennae as well as their proboscis.

Gaining a taste for what is under your feet would not be nearly as exciting as flying, even if it’s mostly nectar. But, scientists studying these explain that butterfly taste receptors don’t just detect sweetness, they also help them distinguish between nutrients and deterrents, probing the plants.

By touching base with the plants, the taste receptors on a butterfly’s feet send a stream of biochemical signals, letting the butterfly know if a plant is a no-go for laying their eggs. Science suggests that butterflies associate bitter tastes with toxins, sticking with the nectar they know and love.

While a person’s sweet tooth may not be healthy, butterflies' sweet feet can be life-saving.

Where do butterflies sleep?

Butterflies are day insects and set up camp to sleep hanging upside-down from leaves. This isn’t just nostalgia for their chrysalis days, hanging on leaves actually protect them from rain and any early morning birds looking to catch a little more than worms.

Butterflies enter a ‘low metabolic state’ at night to conserve their energy and digest food like humans. Scientists differ in their definitions, so this behaviour may simply be a good night’s rest, rather than sleep.

Butterflies with ‘warning colours’ like the orange and black of the monarch and the long-winged tiger and zebra butterflies are less concerned with hiding while they snooze. These colours indicate to predators that they will be poisonous to eat, as they have evolved to store the toxins from the milkweed eaten as caterpillars.

Even with this protection, butterflies aren’t exactly getting shut eye, asbutterflies actually don’t have eyelids. During winter, butterflies press pause on development and effectively hibernate until spring

Butterflies have internal alarm clock telling them it’s time to wake up and return to their usual butterfly activities again. We have no evidence yet that they dream, but science suggests butterflies and moths remember their caterpillar days.

How many eyes does a butterfly have?

Not only will they always win a staring competition, butterflies have eyesight that’s inspired technology developments. They have two 'compound' eyes which bring together thousands of tiny lenses in each eye.

Butterfly eyes contain more light-detecting cells than our eyes, called ‘photoreceptors’, converting light into electric signals that are sent to the brain.Their exceptional eyes allow butterflies to take in information from all directions, keeping an eye out for predators or that perfect flower to land on.

Butterflies have incredible colour vision, arranging these clusters of light-detecting cells like a mosaic. In 2016, scientists found that the common bluebottle butterfly has 15 sets of photoreceptors in each of its bead-like eyes.

The scientists studying these butterflies say sensing this larger range of light lets the butterflies detect subtle changes in colour, which may help with mating or chasing away rivals.

According to ProfessorDoekele Stavenga, who researches insect vision and colouration, the thousands of smaller lenses means butterflies take in as much light as our one big lens.

The efficient little creatures can, however, adjust their vision. Bystacking groups of light-sensitive cells, butterflies modify their vision to be more sensitive to particular part of the light spectrum. Their distinctive eyeshinealso results from interactions with different areas in the light spectrum. It is the light which is not absorbed by these cells, but instead reflected, which causes butterflies' eyeshine.

Understanding the complex workings of butterflies' eyes has already advanced our own optical systems. “The optical principles evolved in nature have inspired improvements of LEDs, for instance, and colour discrimination processing,” says Stavenga.

How many wings does a butterfly have?

Butterflies have four wings. The beautiful patterns on the wings of a butterfly vary across species and have intrigued scientists for decades.

Butterflies havetwo hindwings and two forewings that work together to help them fly, often unpredictable flightpaths helping them escape predators.

Flying would be cool enough, but butterfly wings do more than just carry them through the sky. They can act to attract mates or deter predators, and some butterflies have even evolved to camouflage themselves as leaves.

The colourful patterns of butterfly wings are more than meets the eye themselves. Composed of thin layers of different proteins with millions of tiny scales, butterfly wings gain their colour in different ways.

"Only some are really transparent. Most butterflies have wings with scales that are pigmented, sufficient to make them colourful. Morphos (and many others) are structurally coloured, due to optical multilayer reflections," explains Stavenga.

For such butterflies, it is the particular organisation of tiny structures in their wings which give them colour, not pigments.

Simply, this is when the tiny scales structure themselves in different patterns. When light shines on these patterned structures, they will swallow up some of the colours in the visible light range and reflect others.

So, for morpho butterflies, this can be seen in their blue wing colour, resulting from the arrangement of these cells creating wings which areintensely blue-reflecting. As the blue light has not been absorbed, we can see the beautiful blue colour across their wings.

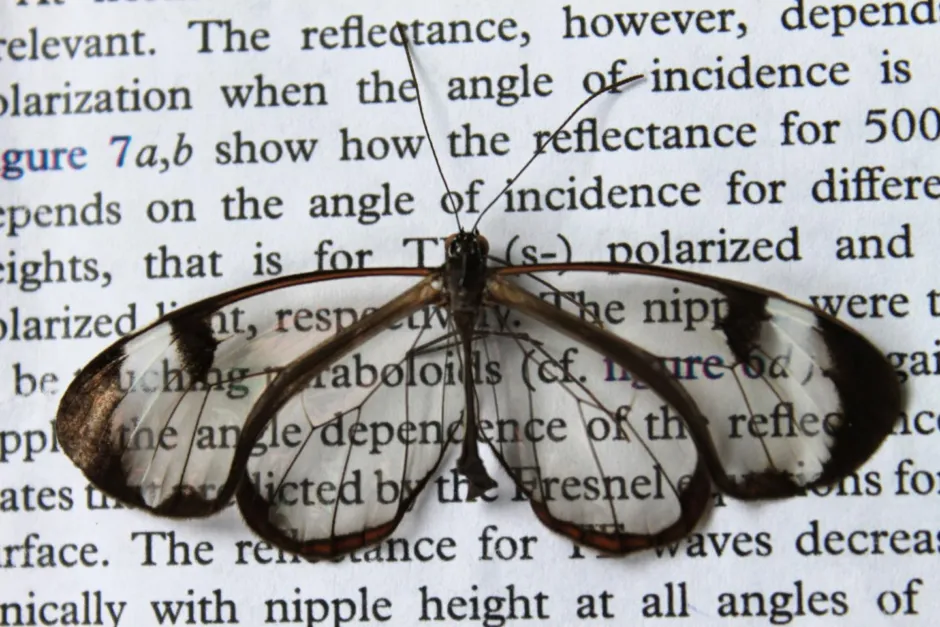

Some species, like the glasswing butterflies, have neither strongly coloured (pigmented) cells or a structure that lends itself to bright reflection and therefore aretransparent.

In 2015, a group of researchers revealed the science behind this transparency. They found that the scales were arranged so irregularly, with nano-structured pillars of random heights, that they barely reflected any light.

Scientists studying these phenomena in butterflies can apply the understanding to developing new smartphone screens. Some researchers have even used CRISPR-Cas9 technology to switch the colour of butterflies' wings, lightening yellow scales to white.

How do butterflies fly?

First, they have to be warm. As cold-blooded creatures, they rely on external sources to regulate their temperature and they can’t take to the sky until their body temperature is around 30°C. So if you see a butterfly bathing in the sun, it’s not getting a tan but warming up its wing muscles.

We have known for years that butterflies wings collide, but just how they fly so well with such a tiny body was a mystery until recently. In early 2021, a team of Swedish scientists shared that butterflies do not flap their wings when flying, but in preparation for flying.

Studying butterflies in a wind tunnel, they observed a distinctive wing clap where they collect and use air. According to the researchers, these butterflies form a pocket and use air to help power their flight.

"It was not exactly what we previously thought, the wings move in a very interesting way. In particular, they have these sort of have cymbal wings," says Professor Per Henningsson, an evolutionary ecologist who published this work.

"Just before the clap, it seems like these wings bend, form like a pocket shape. And then that collapses and they push out again, creating a jet of air, basically.The butterflies benefit from the technique when they have to take off quickly to escape from predators," he adds.

They modelled the behaviour with mechanical wings, classed as flexible and rigid, and found the flexible wings were 28 per cent more efficient in terms of the energy it takes for flight during this clap motion.

Butterfly flight is another aspect where the more we understand, the more technology can advance.

"The shape and flexibility of butterfly wings could be really key to small micro vehicles or drones, that need to be really lightweight and efficient," Henningson says.

Although they study one particular species, he imagines this cupping action occurs across butterflies, and says there is a lot more to learn about their flying manoeuvres in the future.

Read more amazing facts about animals: