Bunny the dog is often in my thoughts. She is mentioned in my replies. My friends talk of her. I see her in newspapers and online articles. And, predictably, she is all over Instagram and YouTube. Why? Because Bunny (for those who have not yet seen her gift) is a dog that can do something most dogs cannot: at the push of a button on a special keyboard, she can express her desires using human words.

Bunny’s YouTube videos show her communicating a range of wants and needs, including 'play', 'food' or requests to go 'outside'. There are even hints that she is capable of grasping sentence structure and word order, a complex linguistic concept only a handful of specially trained animals (mostly apes) have been proven to understand.

So, as someone who writes about the science of dogs, what do I make of it all? Though I applaud Bunny's human companion for her amazing devotion to this wonderful dog, I find myself… surprisingly underwhelmed.

First, because we’ve been here before. As I detail in my book Wonderdog, experimental setups like Bunny's have a rich history, going back to Sir John Lubbock (the 19th-Century inventor of the Bank Holiday among many other things) who trained his poodle to pick up little signs to express his wants ('BONE' – as in 'bone') and needs ('OUT' – as in, 'I need to pee').

Later iterations of the same experiment saw animals trained to use soundboards (much like those used by Bunny, above) or even, in the case of primates, the teaching of American Sign Language, most successfully to Koko the gorilla.

But is this really human language, as you or I understand it? Just as in Lubbock’s time, familiar criticisms about the validity of Bunny's gift are starting surface. The first is about sample sizes. It takes a lot of time to train an animal to use soundboards and this limits the number of dogs involved in repeatable experiments.

Another criticism is that, try as they might, humans (who understandably respond to connection) might see more significance in the one positive button-pressing moment than the nine trials where the buttons pressed made no sense.

Social media brings with it new problems. For instance, how can we be sure that all of Bunny's attempts at communication (good and bad) make it online? And does the fact that soundboards for dogs are now a marketable product give us confidence that everything in the videos is as it is portrayed?

Perhaps the most long-standing criticism of Bunny's experimental setup is that, bluntly, button-pressing animals could, potentially, learn to perform well at the soundboard, regardless of whether they understand that they are using human words or not. To some, this criticism may sound subtle, but it really does matter if we are to objectively understand what dogs may or may not be capable of.

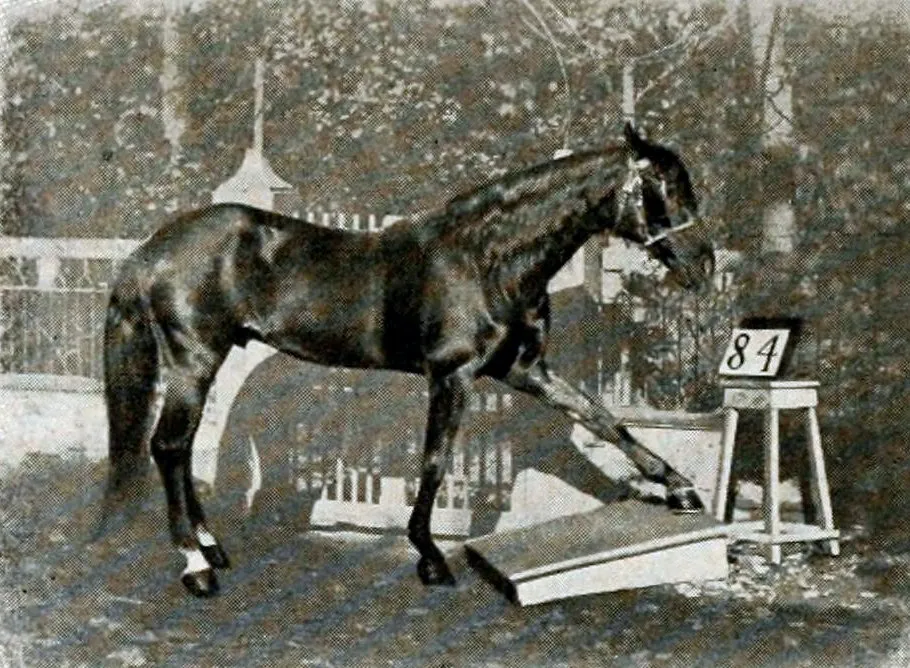

As the canine cognition expert Alexandra Horowitz puts it: “A lyre bird mimicking someone yelling ‘timber’ because they’ve heard someone yelling ‘timber’ is not themselves meaning to say ‘timber!’" I agree with this one strongly, having written about the mistakes science has made in the past – not least with Clever Hans, the maths-whizz horse that wasn’t.

So, I feel a little underwhelmed, yes. But there’s something else too…

As I said, I applaud Bunny's human companion for the love and devotion she shows, but the other something that nags at me is the predictable human-centricity of it all. Why, in Lubbock’s time and in the social media era, are we so intent on dogs mastering the human language? Might our relationship with one another be better served by our getting more acquainted with theirs?

Because dogs, quite clearly, are masters of their own forms of communication, which can be easily read by humans who take the time to look. Want to learn the language of dogs? Then sit, stay… read on…

Read more about dog intelligence:

- Dogs' secret superpower: not intelligence, but love

- Your dog's brain understands words like a one-year-old child

- Dogs perceive their owners' preferences (but do their own thing anyway)

How to speak dog

Dogs are masters of complex communication. Here are some handy tips to help you understand the needs of your loving companion.

Eye contact

Just like humans, dogs use their eyes to communicate. Look for moments when your dog’s eyes are almond-shaped with eyelids partly closed. Look for slow blinks in your direction. These glances are about momentary reassurance and connection between you and your companion.

Warm glances from eyes like these can result in immediate physiological changes to the brains of both dogs and humans. In one study, half an hour of mutual gazing was all it took to see levels of oxytocin (a hormone associated with attachment in mammals) more than double. The effect in humans was even more pronounced.

Wagging

“A tail can be an excellent barometer of what a dog is feeling,” writes Marc Bekoff in Canine Confidential. His advice is to look out for ‘slight wags’ which offer a tentative, “hello there…” to those nearby. Slow wags (at half-mast) can be a sign of momentary insecurity and can be followed by intense, restricted jerking wags which indicate a fight-or-flight response is imminent. Generally speaking, a broad wag is a friendly wag.

Interestingly, dogs wag their tails with a kind of asymmetry that other dogs can pick up on. Left-leaning wags are associated with negative emotions; right-leaning wags, more positive ones.

Barks and woofs

According to the psychologist Stanley Coren, even people who have spent very little time around dogs know the nuances of dog barks, howls and whines and understand what these calls are intended to mean. Deeper barks (which convey larger size and travel further) are reserved for aggression interactions (or, in my case, Amazon delivery drivers); sharp, repetitive barks indicate stress or urgency; a couple of short barks of mid-range pitch often precedes a warm, tail-wagging greeting.

Play-bow

“A stutter bark, which sounds something like ‘Harr-ruff’ … is usually given with front legs flat on the ground and rear held high and simply means, ‘Let’s play!’” writes Coren. This is also known as the ‘play-bow’, another communication tool that dogs use to signal to one another that they are in the mood for fun.

Dogs are so naturally attuned to the play-bow pose that humans, provided they are mobile enough to get on the floor, can elicit play with dogs simply by acting it out themselves.

According to Horowitz (in the illuminating book Inside Of A Dog), the play behaviours of dogs are so complex and constructed that they suggest that dogs are far deeper thinkers than many scientists once thought, perhaps matching (or even exceeding) the complex cognitive skills of our closest relatives, chimpanzees, bonobos and gorillas.

“Their skill at using… play signals hints that they may have a rudimentary theory of mind: knowing that there is some mediating element between other dogs and their actions.” In other words, through play, dogs can consider not only their own thoughts, but also the thoughts of others, and adjust their message accordingly.

This is how dogs really do talk. On their own terms. And they clearly have a lot to say.

Wonderdog: How the Science Of Dogs Changed The Science Of Life by Jules Howard is out now (£17.99, Bloomsbury Sigma).

Read more about dogs: