Our existential context is a microbial matrix. We are continually learning more about how critically important the vast microbial populations everywhere are, not only bacteria but also fungi, viruses, and all the others.

Forms of life are not bad or good; we exist in all our co-evolved complexity, a vast matrix of intertwining life-forms at different scales, interacting, mutually coexisting, and feeding off one another, in ways we are just beginning to recognise.

Mutual coexistence, however perceived (or not), shapes cultural evolution, and since prehistoric times people have learned to work with invisible life forces, such as bacteria and fungi, in the context of fermented foods and beverages, as well as agricultural methods, fibre arts, animal husbandry, and more.

Human cultures around the world have recognised the invisible force of fermentation in mystical ways, as reflected in the gods and goddesses and mythical figures, and the stories and ritual ceremonies found in diverse traditions. There is even speculation that Amerindian healers may have perceived microbes and guided Western science to investigate their role.

But only with increasingly sophisticated tools have we begun to witness and comprehend the complexity of the ecosystems upon, within, and all around us.

From Antonie van Leeuwenhoek’s 17th Century descriptions of animalcules, via Louis Pasteur’s 19th Century innovations in microbial identification and isolation, to modern DNA sequencing and a multitude of new microscopy technologies, we have been able to grasp more clearly, as well as see more vividly, the brilliant diversity of life.

Stemming from my broader obsession with all things fermented, I have developed a passion for photographing fermented foods and beverages in order to see and share their remarkable and awe-inspiring beauty.

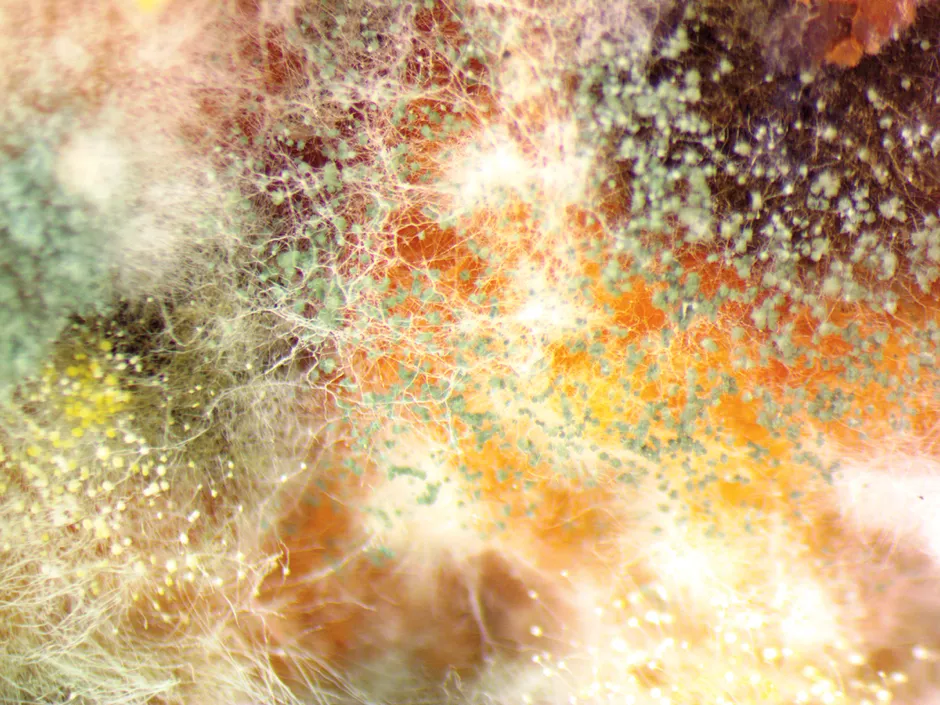

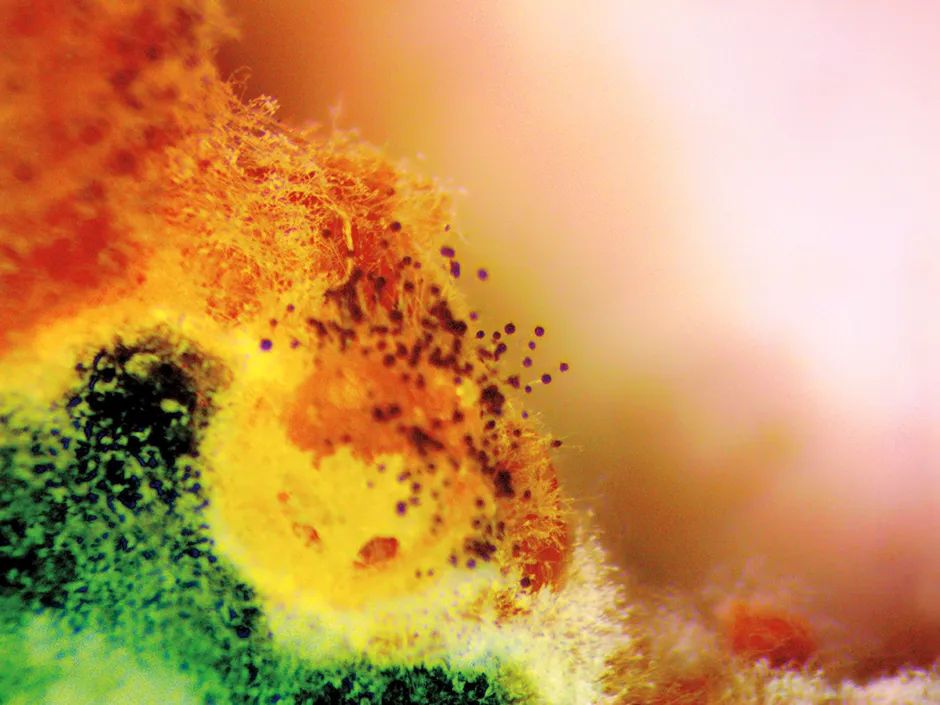

Sometimes I shoot close-ups of especially vigorous bubbles or interesting surface textures. Sometimes I use a stereoscope, also known as a dissecting microscope, which is not quite as powerful as a slide microscope but has a big advantage in simplicity: Instead of having to prepare a slide, I can just place a sample of food under it and focus on the food at different depths, revealing different elements. With filamentous fungi such as koji and tempeh, as well as with random leftover food that gets mouldy, the images captured by the stereoscope can be gorgeous and dramatic.

Unfortunately, the stereoscope’s relatively limited level of magnification and resolution does not render bacteria visible. I have taken photos through my home microscope of slides prepared from various ferments, and bacteria are clearly visible but at fairly low resolution.

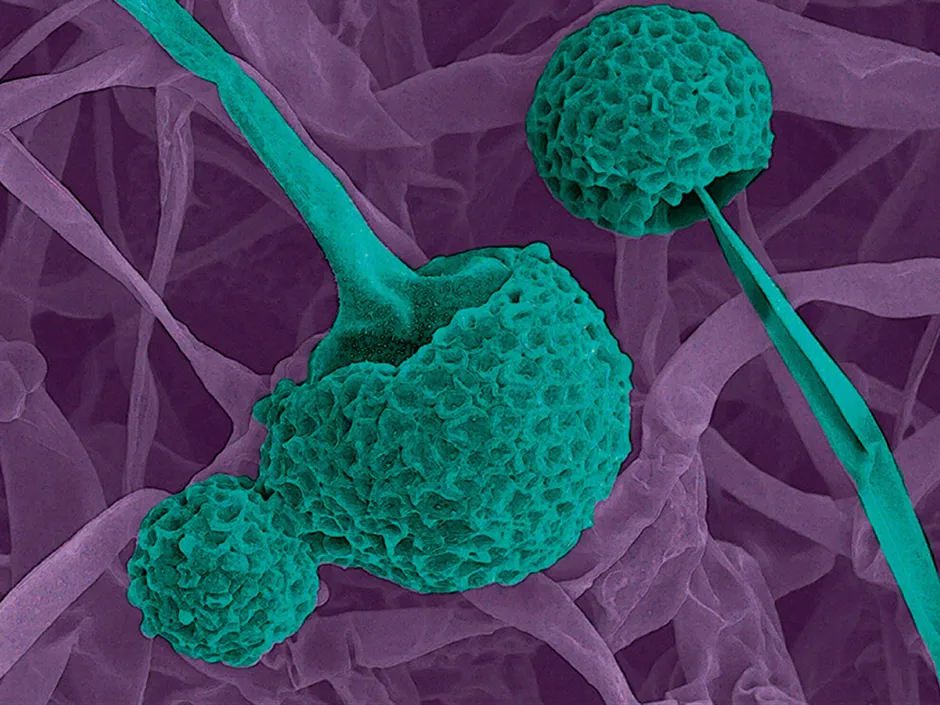

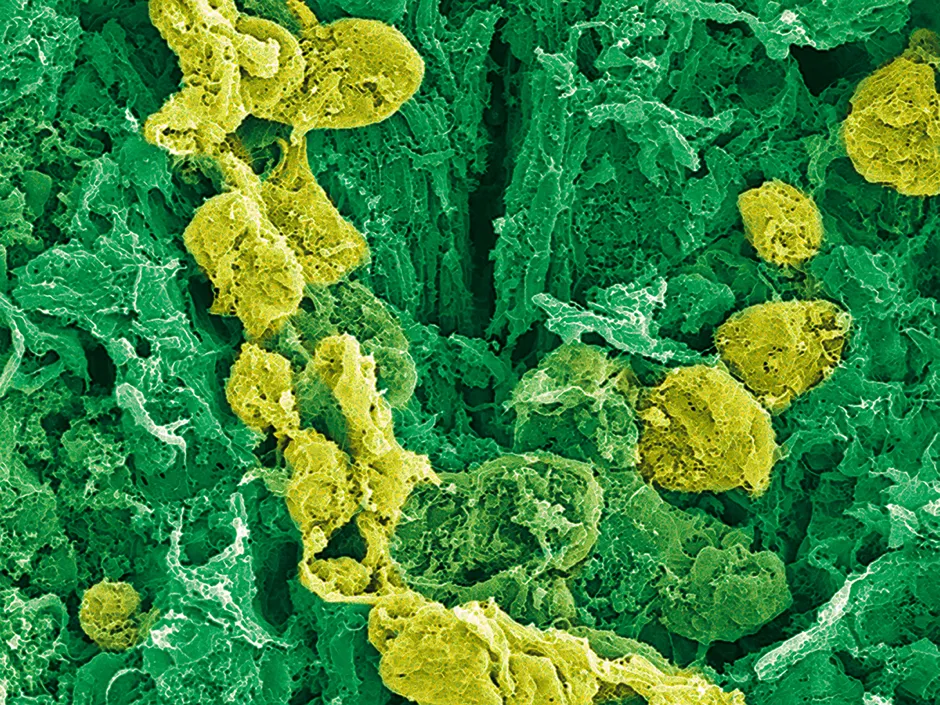

I’ve been extremely fortunate to have been able to access a scanning electron microscope with much greater magnification and incredible resolution, thanks to helpful collaboration with the Fermentation Sciences program and the Interdisciplinary Microanalysis and Imaging Center at Middle Tennessee State University.

Because these images do not use light, they do not convey colour, so for the book we have taken some liberties in colourising them.

These images are not meant to illustrate anything in particular, except for the sheer beauty and complexity of microbial structures and communities. Seeing them takes us far from absolute boundaries and rigid categories.

They force us to reconceptualise. You could say they make us ferment.

Check out some of our other image galleries

- Boxing Weevil scoops top Bug Photography Prize

- The fascinating world of sea slugs

- Slime Moulds: The puzzle solvers without brains

Fermentation as Metaphor by Sandor Ellix Katz is out now (£20.00, Chelsea Green Publishing).

- Buy now from Amazon UK, Foyles and Waterstones