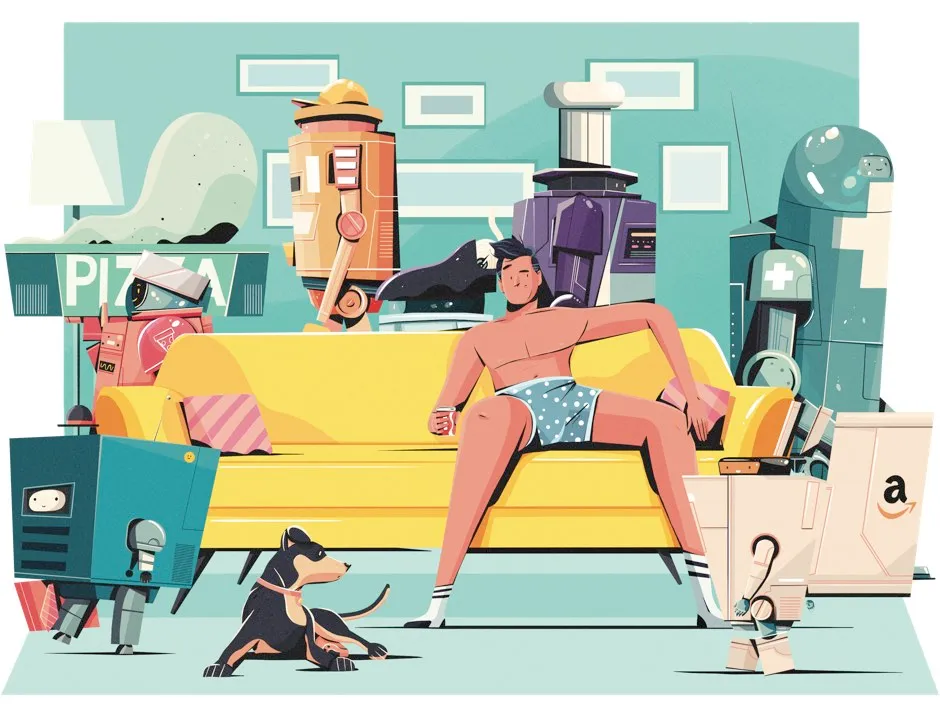

The futurist Martin Ford argues in his 2015 book The Rise Of The Robots that we are headed for a future of “technological unemployment”, brought about by automation and algorithms. Soon enough, our jobs will be taken over by robots, and with artificial intelligence (AI) infiltrating every aspect of our lives, plans are being made for a post-work era. But without a regular routine and a wage, will we slump into sofa-ridden despair, live a life of leisure, or – just maybe – find time to solve the climate crisis?

There will still be some jobs

How many of us will really lose our jobs to robots? A 2018 British Academy and Royal Society report found that 10 to 30 per cent of UK jobs are “highly automatable”, meaning they could soon be done by machines. Manufacturing has already encountered substantial losses; fast food preparation, admin and accountancy jobs are up next, according to the report, while drivers will eventually be replaced by autonomous vehicles. However, the report also predicts that humans will hold on to some lower-paid and manual jobs, such as caring for children and the elderly, and plumbing.

A look to the past suggests we’re unlikely to lose all of our jobs, says Dr Luke Martinelli, a policy researcher at the University of Bath. This was predicted in the 19th Century and again in the 1930s, and it didn’t happen. “So there’s a [view] that humans will always have work – we’ll just do different things,” says Martinelli, suggesting we’ll keep the more creative jobs and those requiring interpersonal skills.

But then, he adds, the more pessimistic stance is that robots could feasibly do anything. On the creative front, for example, machine learning systems are already churning out paintings, sculptures, music and even film trailers that are indistinguishable from human art.

Taken to its logical conclusion, this scenario would eventually see us bowing down before our robot rulers. In fact, New Zealand already has a virtual, AI-powered politician called Sam, who can talk – without mistruth or misrepresentation – to prospective voters, and is reportedly running for parliament in the next election. Maybe that’s one job that robots could do better...

We’d be pretty darn miserable

In 1929, an entire community in Austria became unemployed overnight when the textiles factory that provided work to almost everyone in the village of Marienthal closed down. This became the inspiration for social psychologist Marie Jahoda’s life’s work, crystallised in her ‘deprivation theory’ of unemployment.

Jahoda, who spent many weeks with the locals in Marienthal, proposed an explanation for the hardship people experience when they are unemployed. Work doesn’t just provide money, but also fulfils basic psychological needs including social contact, status and time structure.

Yet no one rigorously tested Jahoda’s ideas until Dr Andrea Zechmann and her colleague Prof Dr Karsten Paul at the Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg in Germany and started speaking to hundreds of people looking for jobs. Their 2019 study confirmed that being out of work causes distress due to seven unmet psychological needs, the most important being collective purpose: work makes our lives meaningful.

This suggests that robot-induced mass unemployment would make us miserable. How miserable? We can only rely on what little we know from long-term studies of unemployment. “People’s wellbeing is on a plateau for months or even some years afterwards,” says Zechmann. “This obviously means that many people who are unemployed for a long time find themselves in a depression.”

Of course, this is in a world where people continue searching for work. What happens without any prospect of re-employment is difficult to predict.

There’d be more time for other things

One way to plug a giant, work-sized hole in our daily schedules would be to fill it with more work, just not of the paid variety. “In a post-work world, what seems important to me is that people can substitute employment with a purposeful activity,” says Zechmann. “For example, this could be engaging in voluntary work, which some people already do, because it pertains to collective purpose – you can work to a greater goal.”

Perhaps we could give our lives purpose by helping the robots to solve some of the world’s most pressing problems. In the days before science became a bona fide profession, there were unfunded or self-funded ‘natural philosophers’.

Even as late as the 1930s, Guy Callendar, who discovered climate change, was more of a hobbyist than a qualified academic. Today, volunteers or ‘citizen scientists’ monitor butterfly populations and beach litter. The jobless could swell the ranks.

Read more about the future of work:

- Meet the robots taking on tasks we'd rather not

- Hacking the economy to prosper in the coming age of artificial intelligence

- How can we stop robots rising up against the human race?

For those who prefer not to spend their free time working, how about looking to the early 1800s for a blueprint of an Austen-esque future where people sit around all day matchmaking and throwing high society balls? Appealing, but few of us would have the money for such extravagances – Mr Darcy was worth roughly £6m a year in today’s money.

Even Callendar, in his leisurely pursuit of climate change data, had the benefit of his steam engineer father’s 22-room mansion and greenhouse laboratory. And matchmaking will probably be done by the robots, anyway – dating apps already use algorithms and machine learning to up our chances of finding a sweetheart.

We’d get money for nothing

In a work-scarce future, the gap between rich and poor is predicted to grow, as a small, tech-savvy elite occupies the few remaining high-paid jobs. A 2019 European Commission report on AI and work highlighted a risk to low-paid and routine jobs, which could “exacerbate inequality significantly”. The report also explores the idea of a universal basic income to help bridge the divide.

Although many versions exist, basic income schemes generally aim to provide people with a regular income to cover essential living costs. Some are totally unconditional, while others depend on meeting certain criteria. Ongoing basic income trials exist, such as a 12-year-long Kenyan project across 120 villages, funded by a US charity.

But as Dr Luke Martinelli, who studies basic income, explains, it’s hard to design a realistic trial. “The Kenyan one is just giving people money,” he says. “It doesn’t consider the other side of the equation where [in the absence of charity funding] the state would have to claw back the money through the tax system.” So in reality, such a scheme could end up being funded by any remaining well-paid workers, through higher tax rates.

The general consensus is that a basic income would provide only enough for a meagre living, meaning many of us would still be seeking part-time work. Martinelli describes it as a “boost” for the worst-off and, for others, a chance to pursue new kinds of work.

There’d probably still be housework

Imagined post-work futures don’t usually take into account all of the unpaid domestic labour that forms a substantial part of our lives. Even if we have a liveable basic income, and a sense of purpose from some kind of community endeavour, we’ll still have the washing up to do and the kids to put to bed.

According to Dr Helen Hester, technofeminism researcher and author of the upcoming book After Work: The Fight For Free Time, the machines we’ve introduced to the household so far have provided only limited relief. This is because we spend any time our household appliances save us on deeper cleaning and increasingly engaging activities for our children.

A 2016 study by Oxford University researchers, for example, showed that in the US, a woman with one child does about two fewer hours of cooking and cleaning a day than she did in the 1920s, but an hour or more of this is reabsorbed into childcare. So it’s likely that, whatever household robots we employ, we’ll still end up carrying out some domestic tasks.

Hester thinks that we could be more open to automating care work at home – for example, using care robots to help us look after children and elderly parents. But she says there’s a “moral value” attached to doing this work ourselves that often leads to us “dismissing automation out of hand”. So perhaps the greatest hurdle to having more robots in our homes is not technological, but our own reservations about handing the work over to machines.

Read more about robots: