On Monday, 15 April, the famous Parisian cathedral Notre-Dame was struck by tragedy when an enormous fire broke out. The blaze was discovered at 18:43 local time, and firefighters tackled it through the night, finally extinguishing it by 10am the following morning. The exact cause of the fire is not yet known, though investigators have suggested that it might have been an electrical short circuit.

World leaders, companies and billionaires pledged money and support for the restoration efforts, and President Emmanuel Macron set a target for the building to be completed within five years, in time for the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris.

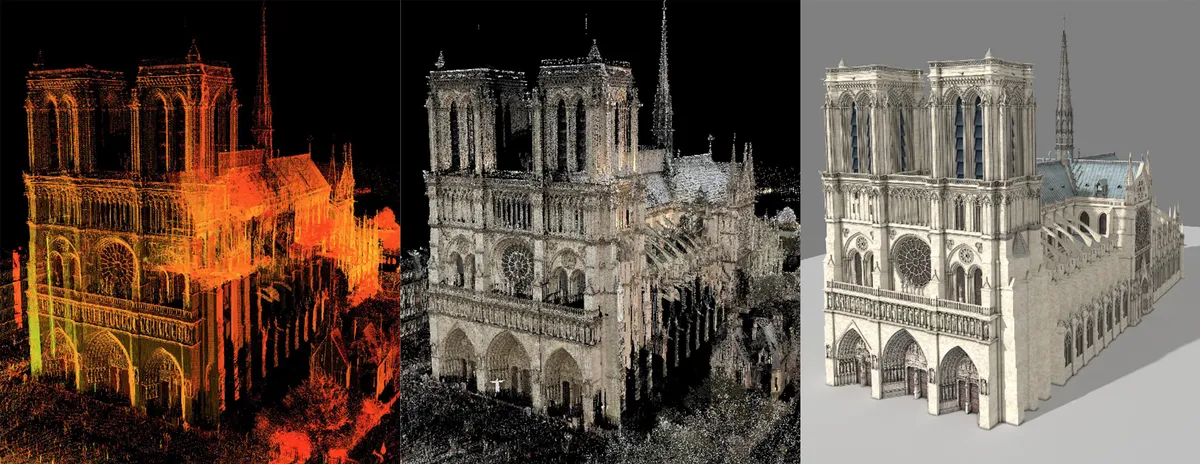

Unlike many other buildings under restoration, the original construction of Notre-Dame is known in exquisite detail, thanks to the work of art historian Andrew Tallon. Tallon, who died in November 2018, catalogued the entire building using the technique of laser scanning.

What is laser scanning?

Laser scanning is a technique that maps buildings and objects in 3D. James Miller, who chairs the Conservation Accredited Register of Engineers in the UK and Ireland, explains: “What it means is that you’ve effectively captured the whole building or structure at its surface. You define precisely where it was. That’s of immense value.” According to Tallon, the scan is accurate to within 5 millimetres.

How is laser scanning carried out?

The laser scanner has a spinning head on a tripod, which is placed at a series of points inside and outside the building. As the head spins, it fires a low-intensity laser and captures it on return. “This beam bounces off the surfaces that it meets and the location of each bounce is recorded,” Miller says.

The scanner measures the time for the pulse of light to return after it has reflected from the surface. The beam’s journey time tells the scanner how far away the surface is. “You might, in some way, liken it to a form of radar,” says Miller, “but it’s a much more sophisticated thing in that it’s locating whole surfaces and large numbers of points in a very short period of time.”

A laser scanner can record up to a million points every second, forming a precise image of the surfaces. The resulting image is a constellation of dots showing the shadow of the building. “It’s a tool that defines geometry. It defines where each stone is – the joints in the stones, virtually,” explains Miller.

The reproduction of Notre-Dame is made up of scans from 50 different angles inside and outside the building, making up a total of over one billion data points. To make sense of the data, Tallon combined the laser scans with spherical panorama photographs taken from the same spot to capture the colours. When the photographs were mapped onto the scanned dots, this produced the ghostly form of the cathedral.

How extensive was the damage to Notre-Dame?

The wooden interior of the cathedral and its spire were both destroyed by the fire. The 13th-Century glass of the three famous rose windows survived, though they sustained some damage.

According to Laurent Nuñez, France’s deputy interior minister, the main structure is in generally good condition despite the fire, thanks to the firefighters saving the building within the last crucial half-hour before it would have been destroyed.

Many of the cathedral’s priceless relics and artefacts were saved, thanks to priests and churchgoers forming a human chain to remove them quickly. Jean-Marc Fournier, chaplain of the Paris Fire Brigade, managed to save the Crown of Thorns, said to have been worn by Jesus during the crucifixion.

Will Notre-Dame be rebuilt exactly the same?

One distinct difference in the rebuilt Notre-Dame will be its spire. Edouard Philippe, France’s Prime Minister, has announced an international competition to design the new spire, saying that they must decide whether it should be rebuilt as it was, or in a way “adapted to the techniques and issues of our era”.

Another factor to consider is whether to recreate the original building’s flaws. Tallon’s scans revealed that the original builders between the 12th and 14th centuries constructed the building around existing structures, resulting in uneven columns and aisles, and Tallon likened the western end to “a total train wreck.”

Miller says that the reconstructed building doesn’t have to have the same inconsistencies. “At Notre-Dame, we have a structure that, like many buildings the world over, it’s breathed, it’s moved, it’s settled, it’s pushed a bit on the corners. Those imprecise, odd corners – what are we going to do about them?” The answer, he says, is to match the new building work with what remains.

“Rather like filling in a big gap where there’s a jigsaw already completed round the edges, we’ve got to decide what to do in the middle. If it used to be a bit crooked in the middle, but the middle is gone, we don’t have to make it crooked. We can build it a little bit more perfect,” he explains. “What you mustn’t do is, when you get to the edges, misalign at that point.”

Could the original building material be reused?

Good conservation practice dictates that as much of the original building material should be used as possible. However, that might not be possible. “I regret to say that, if we’ve had stonework falling, particularly from the ribs of the building, it will be seriously damaged,” says Miller.

Read more:

- Notre-Dame fire “not the worst chapter in its 850-year history” via History Extra

- Notre-Dame: The story of the fire in graphics and images via BBC News

The fall itself isn’t necessarily the source of damage to the stonework. “One of the big problems with fire is firefighting itself,” Miller explains. Cold water hitting hot stone causes thermal shock, which can form cracks in the stone.

Thermal shock is the result of a dramatic temperature change in an object. When cold water suddenly cools a fire-heated stone, the stone contracts rapidly. If it doesn’t cool evenly, then it won’t contract evenly, and micro-fissures can form. These will rapidly spread across the whole object, which will then split apart.

Thermal shock can happen when a hot object is rapidly cooled, or when a cold one is warmed. That’s why an ice cube cracks when dropped in warm water, or a hot frying pan warps when doused in cold water.

How will the building material be replaced?

Good conservation dictates that the new building material should be as similar as possible to the original. “What they will be looking to do is source stone that matches, to look at the quarrying, to look at the type that was used,” says Miller.

The wooden structure, originally made from 1,300 12th-Century oak trees, could be rebuilt with donated wood. Over 100 British stately homes, including Scone Palace in Perth and Belvoir Castle in Lincolnshire, have offered to contribute oak trees.

Visit the BBC's Reality Check website at bit.ly/reality_check_ or follow them on Twitter@BBCRealityCheck

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard