The phrase ‘Made in China’ probably makes you think of poorly-made plastic tat, probably unfairly given the amount of high-end goods coming from the country at the moment (the iPhone being an excellent example). But as James M. Russell discovers in his new book, Plato’s Alarm Clock, which hosts a collection of amazing breakthroughs and devices from throughout history, some incredible inventions have come from the the Far East.

Here are three such inventions that show just how long China has been at the forefront of science and technology.

The Mechanical Clock

First Invented 8th Century AD

Sometimes the joy of history lies in the small details, such as the original names of inventions. The world’s first mechanical clock went by the name of the ‘Waterdriven Spherical Birds’-Eye-View Map of the Heavens’.

Invented by Yi Xing, a Buddhist mathematician and monk, in 725 AD, it was developed as an astronomical instrument that incidentally also worked as a clock. In spite of the name it wasn’t strictly speaking a water clock (one in which the quantity of water is used to directly measure time). However, it was water-powered – a stream of falling water drove a wheel through a full revolution in twenty-four hours.

The internal mechanism was made of gold and bronze, and contained a network of wheels, hooks, pins, shafts, locks and rods. A bell chimed automatically on the hour, while a drumbeat marked each quarter-hour.

Another splendidly named clock was the ‘Cosmic Engine’ built by the Chinese inventor Su Song between 1086 AD and 1092 for an emperor of the Sung Dynasty. This was also a mechanical astronomical clock, but it was huge, spreading over several storeys in a tower that was over 10 metres (35 feet) high. It was made of bronze and powered by water. At the top, a sphere on a platform kept track of the motion of the planets. The clock remained in place and working until 1126 when it was lost in a Tatar invasion.

The Crossbow

First Invented c. 6th Century BC

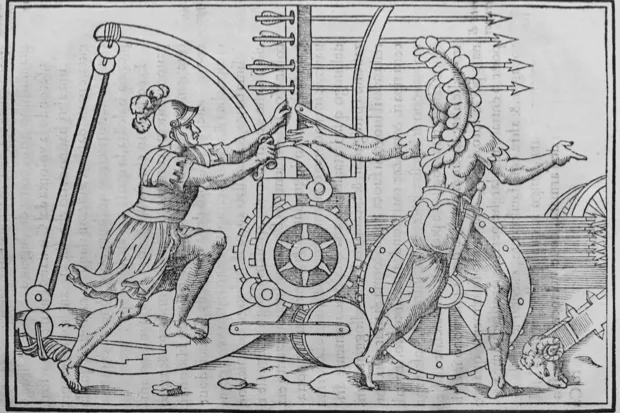

The crossbow is a mechanical application of the bow-and-arrow principle. It generally consists of a horizontal bow (known as a ‘prod’), which is mounted on a stock. The projectiles that it fires are called bolts or quarrels.

Crossbows were another significant step in people’s ability to wage war. While archery was a highly skilled craft that generally had to be learned from childhood by dedicated archers, the crossbow could be mastered by any soldier or new recruit with a few weeks’ training. This enabled far more armies to get up to fighting condition within a short amount of time.

The earliest definite evidence we have of the crossbow comes from the 6th Century BC in ancient China and the neighbouring areas. A 4th-Century BC text mentions a giant crossbow being used in the 6th or 5th Century BC, while Sun Tzu’s classic text on military tactics, The Art of War, which dates to 500–300 BC, mentions the crossbow several times.

When it comes to artefacts, bronze crossbow bolts that date to the mid-5th Century BC have been discovered in burial sites around China, while crossbow stocks small enough to be handheld have been found at a dig in Qufu, Shandong, dating to the 6th Century BC.

A more controversial question is when repeating crossbows were first used. These are crossbows that can rapidly fire multiple bolts. There is some suggestion these might date to earlier, but they are generally credited to the famous military adviser Zhuge Liang (Ad 181–234).

His version, which would be deadly when used by massed ranks of soldiers, could fire two to three bolts at once. It had a magazine loaded with bolts over the bow, and a lever driven mechanism to replenish the bolts. The weapons of this period had a range of about 100 metres (330 feet).

In the medieval period, the Chinese also developed a 12-round repeater crossbow that continued to be used until the nineteenth century, and has been compared to the machine gun in terms of its destructive capacity.

Zhang’s Seismoscope

Date invented 2nd Century AD

A seismometer (or seismograph) is a scientific instrument that measures distant earthquakes and volcanic activity through the tiny movements of the ground that they cause. Remarkably, the first seismometer was invented nearly 2,000 years ago in China. It is known as Zhang Heng’s seismoscope.

Its inventor Zhang Heng thought that the main cause of earthquakes was chaotic air motion, theorizing that:

... as long as [air] is not stirred, but lurks in a vacant space, it reposes innocently, giving no trouble to objects around it. But any cause coming upon it from without rouses it, or compresses it, and drives it into a narrow space ... and when opportunity of escape is cut off, then ‘With deep murmur of the Mountain it roars around the barriers’, which after long battering it dislodges and tosses on high, growing more fierce the stronger the obstacle ...

In Zhang’s device the earth tremors made a bronze ball fall out of any one of eight tubes (in the shape of dragons’ heads). The ball then fell into the mouth of a metal toad, whose position indicated the orientation of the seismic wave.

It isn’t fully known how the device worked. The eight mobile arms definitely raised a catch via a crank, and a lever, which released the ball. Apparently the device also included a pendulum hung from a bar. This suggests that the driving force was inertia – a small movement in the pendulum perhaps triggered the motion that was transformed into a slight force on the correct lever.

However, there are no clear historical documents or remaining examples, so modern attempts at reconstructions involve a considerable degree of speculation and interpretation of the few mentions that were made of the device in contemporary texts. Nonetheless, it seems clear that Zhang’s seismoscope did use similar technology to early modern seismographs.

After the death of Zhang, it was not until 1783 that a simple seismograph was deployed by an Italian scientist called Schiantarelli, who used it to measure a major earthquake in Calabria.

Zhang Heng, the Chinese Da Vinci

It’s worth taking a moment to celebrate the life of Zhang Heng (78–139 AD), whose expertise across a wide range of fields – including maths, science, engineering, cartography, art and poetry – have led to him being described as the Leonardo da Vinci of ancient China.

He was initially a minor civil servant, but rose to become the Chief Astronomer and Palace Attendant at the imperial court. As well as his seismoscope, he invented a water-powered astrolabe (a three-dimensional model of the solar system), gave an improved estimate for the number pi, and catalogued over 2,500 stars.

He also gave an advanced description of the Moon, its ‘dark side’, and how lunar and solar eclipses proved that the Moon must be a spherical object. And if all that wasn’t enough for one individual, he was also a renowned poet, whose work was still being studied years after his death.

Plato’s Alarm Clock and Other Amazing Ancient Inventions by James M. Russell is out now in hardback, (£9.99, Michael O’Mara Books)

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard