Stepping through the heavy, air-locked door into the world’s most advanced indoor vertical farm, it’s the noise that hits you first. It’s loud. Machines buzz and whir over the insistent drone of the warehouse-scale air circulation system.

The lights are dazzling. Peering up at the two-storey-high living curtains of plants quickly prompts a protest from your neck. Nearby, a few workers, wearing coveralls, hair nets, hard hats and earplugs, keep a cool eye on their busy robot underlings. The air is bright with the fresh, sweet scent of tender young salad leaves.

It’s a far cry from the story-book picture of a farm; there’s no mud, no wellies, no hens pecking in the yard. But the owners of this facility, a San Francisco-based company called Plenty, claim the system they’re pioneering inside this warehouse in Compton, Los Angeles, can produce up to 350 times the yield compared to a field of the same size.

What’s more, they say their system uses just 10 per cent of the water and zero pesticides – and that it can be replicated almost anywhere.

The new farm in Compton grows four types of leafy greens: baby rocket, crispy lettuce, baby kale and curly spinach, and has the potential to produce up to 2 million kg (4.5 million lbs) of food annually, in the space of a single city block.

Read more:

- What is vertical farming?

- Down on the robot farm

- Could farming without soil help solve the world's food crisis?

If it lives up to its promise, the approach could revolutionise the way humanity feeds itself. That’s why the crew filming the ‘Humans’ episode of Planet Earth III was on site a day after the farm began operating, so that audiences around the world could see for themselves.

The episode takes an unflinching look at the effect our species is having on the planet.

“The biggest challenge facing the natural world from the human world, right now, is habitat loss,” explains producer-director Fredi Devas. “And the biggest area of habitat destruction comes from agriculture.”

Today, half of the world’s habitable land is used for farming. More than three-quarters of that is used to rear animals, yet meat and dairy make up only around a third of the world’s protein supply and provide less than a fifth of its calories.

As the world’s population grows, our supply of cultivable land is dwindling and we’re encroaching further into other species’ homes. We urgently need to figure out how to keep up with the increasing demand for food. Do vertical farms like the one at Compton hold the key?

From seed to shop

At Plenty’s Compton farm, every step of the process, from seed to shipping, is automated. From the moment that a worker tips a bag of seeds into the drum of the seed-sowing machine, the machines take over.

First, the seed-sower drops seeds into trays filled with a soil-free coconut husk substrate. The trays are sprinkled with water and whisked away on a conveyor belt for a two-day stint in a darkroom, where they’re kept in humid conditions to encourage the seeds to germinate.

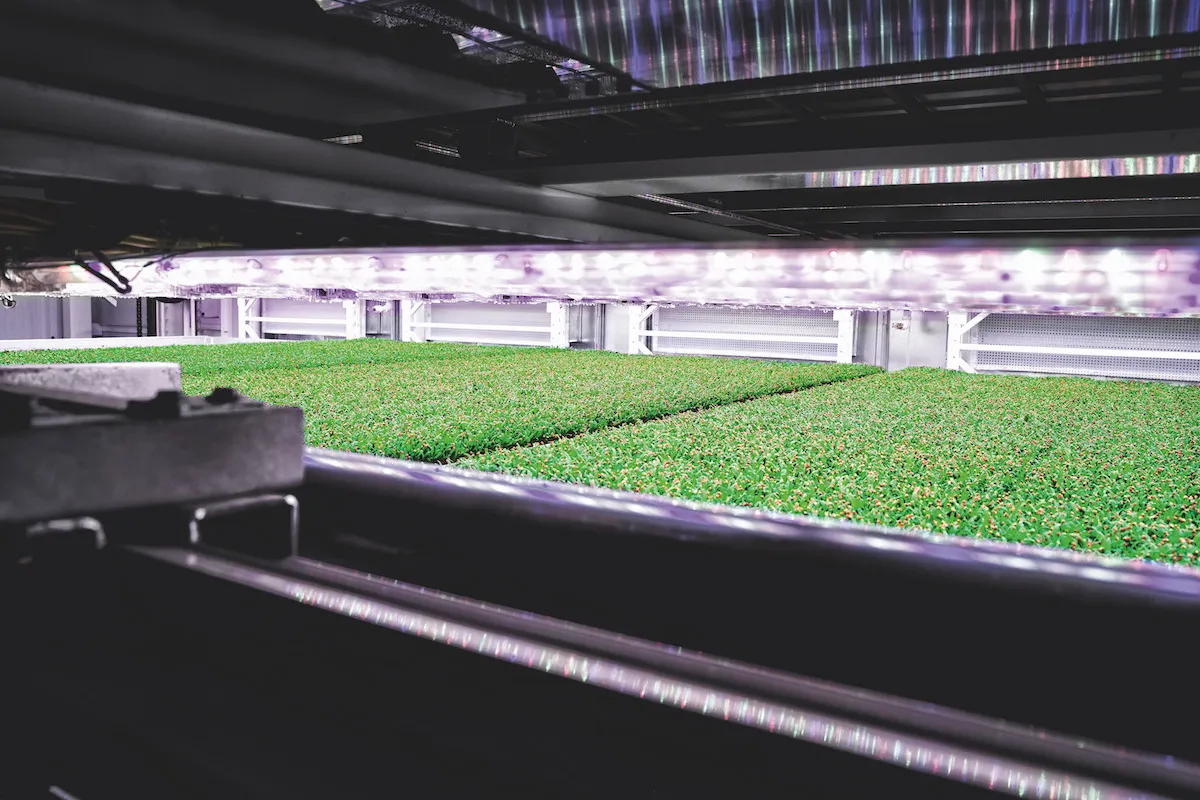

Once the seedlings emerge, the trays are sent to a vast propagation room. Here, the baby plants spend a couple of weeks stacked in horizontal racks, bathed in a carefully curated spectrum of LED light and receiving a bespoke cocktail of nutrients that kick-start the growing process.

Within two weeks of being sown, the young plants have a robust set of first leaves and their roots have wound their way down through the substrate, forming neat little plugs.

A bank of white robot arms, each fitted with a row of pincers, are surprisingly gentle as they pluck the plants and their plugs from their trays. In unison, the arms turn and nestle the plants into evenly spaced holes along a skinny 10m (32ft) section of metal track.

Except this isn’t a track, it’s a tower – a fact that suddenly becomes clear as an enormous yellow robot arm grabs it, swings it through 90° and hangs it from the ceiling.

From here, the tower trundles down a corridor to the grow room, where it’ll spend the next couple of weeks under precisely controlled light, water and nutrient conditions, gradually advancing along the runners as each of the towers ahead of it is taken off for harvest. By the time it reaches the front of the queue, it’s brimming with plush green leaves.

Down another corridor, in the harvest room, a robot arm unhooks the tower and lays it flat before zipping it through a set of rotating blades.

The harvested leaves tumble through an advanced optical sorting machine, which uses AI and special wavelengths of light to check each leaf for damage. Any that don’t make the grade are popped off the conveyor belt and into the waste pile by a targeted puff of air.

The rest are packaged on the spot; since they’ve never been in contact with soil, pesticides or human hands, there’s no need to wash them.

The produce harvested here is trucked five minutes down the road to downtown Compton’s Walmart, or to Wholefoods stores around Los Angeles.

Plenty’s greens go from seed to shelf in little more than four weeks – less than half the time it typically takes for the same products grown outdoors. And because everything about their environment is controlled, they can be grown year-round, at peak-season quality.

Bright lights

Vertical farming isn’t new. The idea of maximising a given footprint of land’s growing potential by stacking plants indoors was developed in the early 2000s by Columbia University professor Dickson Despommier and students in his medical ecology class. Since then, hundreds of start-ups and investors have attempted to turn the concept into a viable, scalable method of food production, but none have succeeded.

“Number one, they had the wrong architecture,” says Nate Storey, co-founder and chief science officer at Plenty.

The artificial lighting that plants need to grow indoors without sunlight produces heat. A lot of it. The brighter the lights, the more heat they produce. Growers have struggled to protect their stacked plants from the heat rising from the layers below and found the cooling costs of vertical farming crippling.

The seed for Storey’s big idea was sown more than 20 years ago, as he tinkered with organic systems at the University of Wyoming. One of his trials involved testing how well plants would grow in towers.

“At a plant level, the performance was terrible,” he says. “But on a square foot production basis, the performance was very high. And I thought: there’s something to this.”

The beauty of truly vertical architecture is that air can circulate freely, allowing natural convection to carry heat up and away, rather than trapping it between horizontal shelves. That switch means Plenty can use powerful LED lighting that mimics the Sun.

“We’re able to put three, four or five times as much energy into the space as someone else can, which means we get three, four, five times as much energy out for every dollar of hardware in the facility,” says Storey. That “energy out” is the energy the plants use to grow. Five times the energy in; five times the yield.

The facility at Compton is the culmination of more than nine years of research to optimise every possible aspect of the process and the product, from flavour to crunch. The facility opened on 18 May this year and the Planet Earth III crew was there to film it.

But persuading a company to let you fly drones around millions of dollars’ worth of brand-new equipment is a tall order. The negotiations took six weeks, with Devas’s proposal going in front of Plenty’s board at least twice.

Read more:

- Which vegan milk is best for the environment?

- Are there any crops that can be irrigated by salt water?

- Is peat-free compost better for the environment?

What swung it was a video Devas sent over of the man they had in mind for the job, world-class drone operator Zach Levi-Rodgers, flying drones at breakneck speed in and out of equipment in a gym. “I think from that they understood. ‘Okay, if he can do that…’ It put their minds at ease,” says Devas.

Unusually, for wildlife filmmaking, it was easy to capture smooth, gliding ground shots, thanks to the level floors. But there were new challenges to contend with, including figuring out which camera settings would prevent all the frequencies of light on the farm causing the images to flicker.

To meet the farm’s strict food safety standards, four crew members spent an entire day pre-shoot sterilising each piece of equipment: trolleys, gimbals, sliders and rigs, nine cameras, and every last lens cap and screw.

On the day of the shoot, they suited up like the farm workers, donned gloves, shoe covers and goggles, and finally stepped through the air-locked door. “It really genuinely felt like a vision of the future,” says Devas. “It was very strange to see these towers of produce just moving, with no-one around.”

Of course, they couldn’t leave without tasting the goods. “I grow my own food, totally organically, on my allotment,” says Devas. “And this food at Plenty tastes absolutely exceptional.”

Growth strategies

Plenty’s staff includes nearly 80 plant scientists. It’s their job to decipher the optimal growing conditions for each plant and feed that information back to the company’s more than 100 hardware and software engineers.

“Plants are really just little software programs,” says Storey. “The DNA of a plant tells it what to do… what to build, how to react to the environment around it.”

By building a deep understanding of each plant’s physiology, Plenty’s scientists have learned how to push the buttons of the plants’ DNA – without modifying it – to program qualities like growth, flavour, texture and nutrition. For instance, hitting a plant with light at the bluer end of the visible spectrum, at the right point in its growth cycle, gives its leaves a satisfying crunch come harvest time.

Plenty has invested heavily in proprietary LED lighting systems that deliver what Storey calls, “the best parts of the Sun”. Plants thrive on sunlight, but they don’t use the entire spectrum to grow and develop flavour. Using a targeted spectrum of light, Plenty provides every wavelength the plants require, while also reducing the lights’ energy demand and a little of the heat that they generate.

Traditional agriculture consumes 70 per cent of the planet’s freshwater each year. On the Compton farm, the water supply is controlled on a plant-by-plant basis, and the vapour that evaporates from their leaves is condensed and put back into the irrigation system.

The approach means that the farm uses less than a tenth as much water as field-based farms. It’s a major boon in Compton’s drought-stricken home state of California, where the main source of water (the Colorado River) is rapidly running dry. Meanwhile, the sealed environment means the Plenty crop can be grown completely pesticide-free. That means no washing, on the farm or at home, and no agricultural runoff.

A step in the right direction

The electricity needed to power and cool farms like the one at Compton mean that, for now, they’re not a silver bullet to the climate crisis. But the grid is greening at a faster rate than anyone predicted, says Storey. Meanwhile, the environmental cost of conventional farming is only rising.

Climate instability is already having a disruptive impact on food supply. In the US, extreme weather events such as floods, storms, droughts and wildfires destroyed more than $21 billion worth of crops in 2022, making it the third costliest year on record.

But indoor farms are protected from extreme weather, which means they could have an immediate role in climate resilience and food security. Of course, the world can’t live on lettuce alone. And staples such as wheat, and protein crops like soybeans are still a long way off being economically viable in the indoor setup.

Nevertheless, as companies like Plenty expand their range of crops, land that was once farmland can be returned to nature, giving it a chance to bounce back.

“I view what we’re doing as providing an alternative… to tilling up more soil, to cutting down more trees,” says Storey. “If we can take pressure off marginal agricultural lands, and turn those back into wild spaces, that’s the ultimate contribution to biodiversity.”

Devas is also cautiously optimistic about vertical farming. A committed vegan who has witnessed, up close, the Amazon rainforest being cleared to make room for cattle grazing, he sees its potential for breaking the link between the growing need for agricultural land and species loss.

In the ‘Making Of’ reel that accompanies Planet Earth III’s ‘Humans’ episode, his impression of Plenty’s Compton farm is caught on camera: “It does feel like a really good start.”

About our experts

Fredi Devas is an Emmy-nominated BBC television producer and director who has worked on iconic science shows such as Frozen Planet and the Planet Earth series.

Nate Storey is the co-founder and chief science officer at Plenty.

Read more: