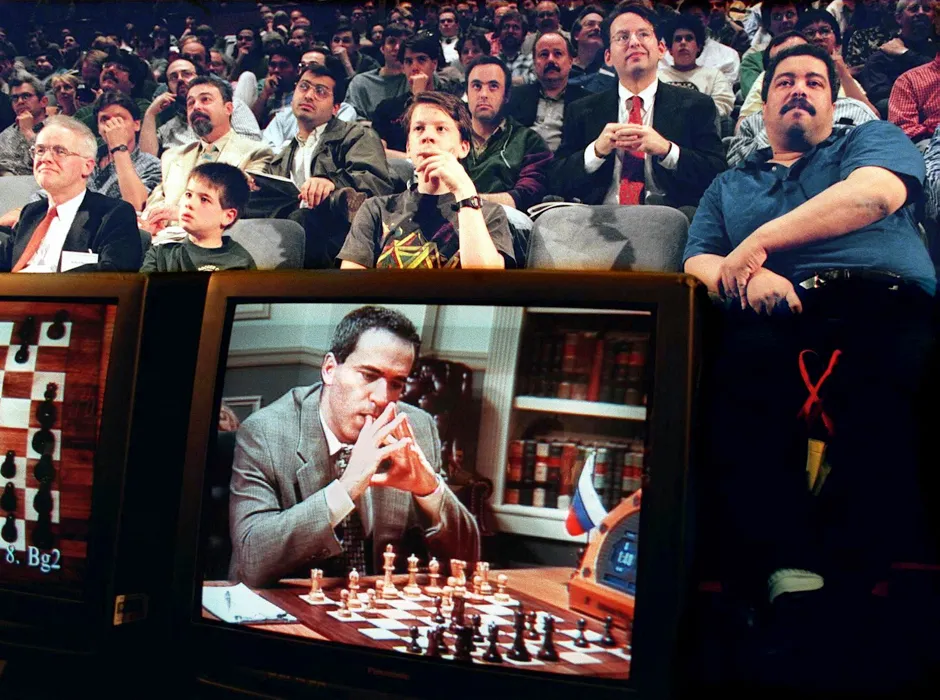

Chess, a board game played throughout the world, has pitted some of the greatest minds in battle for hundreds of years, but since Deep Blue defeated chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov, artificial intelligence systems are now taking the spoils. In 2017, one such AI system, AlphaZero, became the strongest player in chess history, beating the existing world-champion chess computer after only a few hours of training.

In the new book Game Changer, Grandmaster Matthew Sadler and Woman International Master Natasha Regan investigate the inner workings of AlphaZero, how it devises strategies, and why Demis Hassabis, founder of artificial intelligence company DeepMind, turned to chess to test the power of its AI system.

Ahead of its publication, we have an exclusive extract of the introduction by Demis Hassabis, where he reveals how chess changed the way he thought about creating artificial intelligence, why games are a perfect testing ground for AI, and how AlphaZero-like learning systems could shape our future away from the chess board.

Far from being just a game, chess has always been a part of me.

I started playing when I was four, and as I rose up the England junior ranks my dream was to become a world champion. Playing the game seriously at such a young age was an extremely formative experience. It taught me how to solve problems, how to make plans and devise strategies, how to deal with the intense pressure of competition, and how to imagine and visualise possible futures. In essence, chess taught me how to think. But as I strove to improve as a chess player, I started to deeply introspect and wonder about the nature of thinking itself. How was my brain coming up with these moves, and what was behind this phenomenon we call intelligence?

These questions led to my lifelong obsession with the workings of the mind and a fascination with philosophy and neuroscience, but one particular moment would end up having a big impact on the direction I would take for the rest of my life. I was 11 years old and in the middle of a gruelling eight-hour match with a veteran Danish master at a big international tournament in Liechtenstein. We had reached a highly unusual endgame, which I had never seen before – I only had my queen, and my far more experienced opponent had a rook, bishop and knight. He was ahead in material but if I could just keep his king in check with my queen, I could force a draw. Hours rolled by as he pushed his pieces around trying to outmaneuver me, and the vast playing hall slowly emptied as everyone else finished their games. Then suddenly, after dozens of moves of not making any progress, he finally somehow managed to trap my king, with checkmate seemingly forced on his next move. Exhausted and shocked, I resigned.

Immediately he stood up, perplexed. He laughed as he dramatically gestured that I could have secured a draw if only I had sacrificed my queen, to achieve a stalemate. At the last moment he had just tried a final cheap trick, and it had worked! I felt sick to the pit of my stomach. The next day I reflected over what had happened, and as I looked out over the packed hall filled with brilliant minds, I vividly remember wondering, what if all this incredible collective mental effort being expended could instead somehow be channelled into something beyond games, perhaps an important area of science or medicine, what might it be possible to achieve?

That epiphany marked the beginning of the end of my professional chess career, but also sowed the initial seeds for what would eventually become DeepMind, the artificial intelligence (AI) research company I co-founded in 2010. And while I didn’t become a world champion or even a professional player in the end, the transferable skills I honed through chess have continued to influence and inform all aspects of my life, and that is why I’m always very encouraging of children being taught chess as part of the school curriculum.

In fact, a chess connection was even partly responsible for attracting our first major investor. Back in 2009 AI was not the hot topic that it is today and we were trying to get a meeting with a well-known Silicon Valley venture capitalist to pitch DeepMind. After many requests, we eventually managed to snag an invite to speak at an AI conference where we would have a chance to briefly meet him. Unfortunately, so would hundreds of others who also wanted to pitch their business idea. I knew we would have to do something unique to stand out from the crowd but wasn’t sure what. During my background research, I had read that he was a strong chess player, so when our turn finally came around to briefly speak to him I decided to forgo the details of the company we wanted to create and instead discuss chess. I told him that – in my opinion – it was the exquisite balance of the bishop and knight across the set of all positions, despite their vastly different mobility, that creates the dynamic tension in the game. It was a risky strategy but, suitably intrigued and his interest piqued, we got our full pitch meeting the next day and off the back of that he invested in the company!

Our ambition at DeepMind is to build intelligent systems that can learn to solve any complex task by themselves, and then use this technology to help find solutions to some of society’s biggest challenges and unanswered questions. Put another way, we want to solve intelligence and then use it to solve everything else. And on the path towards that ultimate goal we, perhaps surprisingly, use games.

Games are designed to be challenging for humans to master and usually represent some interesting aspect of the real world. We think they are the perfect platform to develop and test ideas for AI algorithms. It’s very efficient to use games for AI development, as you can run thousands of experiments in parallel on computers in the cloud and often faster than real-time, and generate as much training data as your systems need to learn from. Conveniently, games also normally have a clear objective or score, so it is easy to measure the progress of the algorithms to see if they are incrementally improving over time, and therefore if the research is going in the right direction.

Using this approach, we’ve already had many notable successes including DQN, a learning algorithm that achieved expert-level scores on a range of classic Atari games with just the raw pixels as inputs; as well as AlphaGo, the predecessor of AlphaZero that became the first computer program ever to beat a professional player at the ancient and complex game of Go, a feat considered by many to be a decade ahead of its time. The 2016 match that AlphaGo won against the legendary Go champion Lee Sedol in South Korea turned out to be a major landmark for AI, but it was the original way that AlphaGo played that completely astounded the experts. Most famous of these novel ideas was Move 37 in Game 2, which will probably go down in Go history. It was a move so unthinkable, that some of the world’s top Go players who were live commentating thought there must have been some sort of mistake, and yet more than 100 moves later this stone turned out to be in the perfect strategic place to decide the outcome of the game. After the match Lee Sedol said, ‘When I saw this move... I [thought] surely AlphaGo is creative.’ This motif and many other ideas AlphaGo revealed have subsequently overturned centuries of received wisdom about the game, and many experts feel that it has ushered in a new era for Go.

Building on the success of AlphaGo, in 2017 we began working on our latest and most ambitious project yet, and the subject of this book, AlphaZero. At DeepMind we believe one of the keys to AI is the notion of generality, whereby a single system is able to perform well across a wide variety of tasks, much like the brain. AlphaZero was our attempt to generalise AlphaGo to play any two-player perfect information game. And of course the obvious thing to try it on first was chess!

The relationship between chess and AI is as old as computer science itself. The early giants of computing, and some of my all-time scientific heroes – Turing, Shannon, Von Neumann – all tried their hand at writing chess programs. From a personal perspective, it also felt like something of a homecoming, bringing me back full circle to the game that had first sparked my curiosity about intelligence. But I also had doubts. Unlike with Go, of course IBM’s groundbreaking Deep Blue program had long proven chess could be mastered by computers. Subsequently its legion of successors, including Stockfish, Komodo and Houdini, have become extraordinarily strong. But all these programs rely on thousands of hardcoded rules and heuristics painstakingly handcrafted by human experts over years of work. By contrast, AlphaZero is nothing like these programs. It is entirely self-taught and learns to play chess completely from first principles. Given just the rules of the game, AlphaZero starts from totally random play, and gradually improves through a sophisticated version of a trial and error process, by playing several million games against itself and incrementally learning from its mistakes.

When we started the AlphaZero project it was far from clear that a program of this type could possibly hope to compete with the specialist handcrafted chess engines that had decades of cumulative effort spent on them from some of the best computer scientists and chess grandmasters in the world. In fact I remember discussing this very question with Murray Campbell, one of the original engineers of Deep Blue, at a conference in early 2016, before the Lee Sedol match and before we had started AlphaZero. Had modern chess engines already reached the absolute upper limit that chess could be played at – could they be beaten? Was there enough room in the game to find something more, some new dimension? Both of us were unsure of the answers, and in my experience, these kinds of scientific questions, where either outcome would be interesting, are the most worthwhile ones to pursue.

Incredibly, it turned out the answer to these questions was a resounding yes! And after just a few hours of training (albeit utilising a big cluster of computers) AlphaZero reaches the phenomenal strength you will see in the games in this book, to arguably become the strongest chess program in history. When I first saw some of AlphaZero’s games I was blown away by how it played, and I hope you will be too. From the outset, it was clear that AlphaZero played very differently to traditional chess engines, with fluid, human-like attacking play. For me, as somebody who loves chess, there was something deeply satisfying about witnessing this dynamic and aesthetically pleasing style of play emerge, reaffirming the game still has a wealth of secrets left to be discovered.

In this book, Matthew and Natasha have brilliantly elucidated AlphaZero’s unique style of play. They uncover fascinating new insights into all facets of chess from piece mobility to king safety to daring sacrifices and so much more, which I hope will be of interest and benefit to chess players of all levels. By speaking at length with the researchers who developed the machine learning techniques underlying the system, Matthew and Natasha have gained a deep understanding of how AlphaZero ‘thinks’, and I have been impressed with the clarity and simplicity of their explanations of the technology. They have also placed these modern ideas very carefully into their correct historical context, by illuminating the reader with intriguing analogies to the styles of the great champions of the past. My hope is that the games and analysis in this book will help to spark a new era of creativity in chess, and that players will not only incorporate some of these ideas into their own games, but also be inspired to find new styles of their own. I can certainly attest that through this project my own passion for chess has been rekindled, and it has been thoroughly enjoyable to revisit an old realm I once knew well, but now see through an entirely new lens.

Of course this book is not just about the beauty of chess, but also the incredible potential that AI holds. I hope that after reading it you will get a sense for some of the wonder and marvel we all feel, thinking about and working on these enthralling topics every day. AlphaZero is just the beginning for us. I hope it has given you a glimpse into a bold and bright future, where we have a myriad of AlphaZero-like learning systems helping us as a society to find new breakthroughs in critical areas of science and medicine, just like I once dreamed of as a small boy in a vast chess hall, half a lifetime ago.

Demis Hassabis,London, October 2018

This is an extract fromGame Changer: Alphazero's Groundbreaking Chess Strategies and the Promise of AIby Matthew Sadler and Natasha Regan, published on 25 January (£19.95)

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard