Dr Lara Martin wants to teach artificial intelligence how to tell a tale and tell it well.

Lara is a Computing Innovation Fellow postdoctoral researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, where she teaches AI to generate stories and produce language that is natural and human-like.

She reveals why we need to train machines how to be storytellers and what Dungeons & Dragons has to do with it all.

Why do we want to teach machines how to tell stories?

People have been telling stories since before we could write; we’re natural storytellers. So if machines were able to tell and understand stories as well, we’d be able to communicate with them more naturally.

We’re starting to adopt conversational personal assistants – like Alexa or Siri – as a society, but these computers still don’t actually know how to converse. The most effective and personal way people have of conversing is by telling stories.

So teaching an AI to tell stories could improve our lives and technology?

A lot of people don’t realise how much nearly everything we say is a story, or could be framed as a story. I like imagining that you could just talk to your personal assistant, and it would work with you to figure something out.

Like maybe you’re planning a birthday party for your kid, and you tell it “Hey, I’m planning a party for Gina’s 10th birthday. Can you help me?” and it can create a story about this party: “Every good party starts with cake. You could get a cake at the local grocery store, and then while you’re there buy some balloons. Once you’ve set up the decorations...” and so on.

The assistant could collaborate with you to come up with this party narrative until you’re happy with it. I think there’s a lot of cool potential for human-AI collaboration here.

Where do you start? And what are the layers you need to build to teach an AI about telling stories?

There are a couple of ways to start. Most modern techniques start with a tonne of stories. You collect or find a bunch of stories, and run them through an algorithm that memorises patterns in the stories, such as fighting the dragon usually comes before saving the princess, for example. Then you – the human – come up with the first sentence of the story and it’ll spit out the rest.

These systems tend to be really good at generating brand new, grammatical English sentences, but they just ramble on and forget what they were talking about after a little while.

The earlier techniques – which some people are still working on – take a lot more effort to make. These researchers sit down and come up with all of the possible plot points in a story world and how they would connect. The system would then plan out a path to take through these plot points in order to create a story.

There isn’t as much focus on the language itself because they can just have a sentence or two already ready to display for when the system picks that plot point. They focus on the cause and effect of the plot points in the story: for example, ‘Veena needs to get a sword before she can slay the dragon’. Note this is subtly different from the modern methods.

My PhD thesis was about combining various ideas from these two methods. I would take the text generated by the new techniques, and throw it through some rules and constraints, like in the older techniques, to make sure it’s actually a possible next sentence for the story.

What kind of story can computers tell?

The older methods create really coherent, detailed stories, but you can only tell stories using the stuff created by hand, which can mean that you can tell really rich stories within a single story world. One of my favourite examples of this is a game called Façade created at the University of California, Santa Cruz. You can also think of these types of stories like playing a giant open-world game – like Skyrim or The Witcher – where all the branches in the story are created or managed by AI instead of a human.

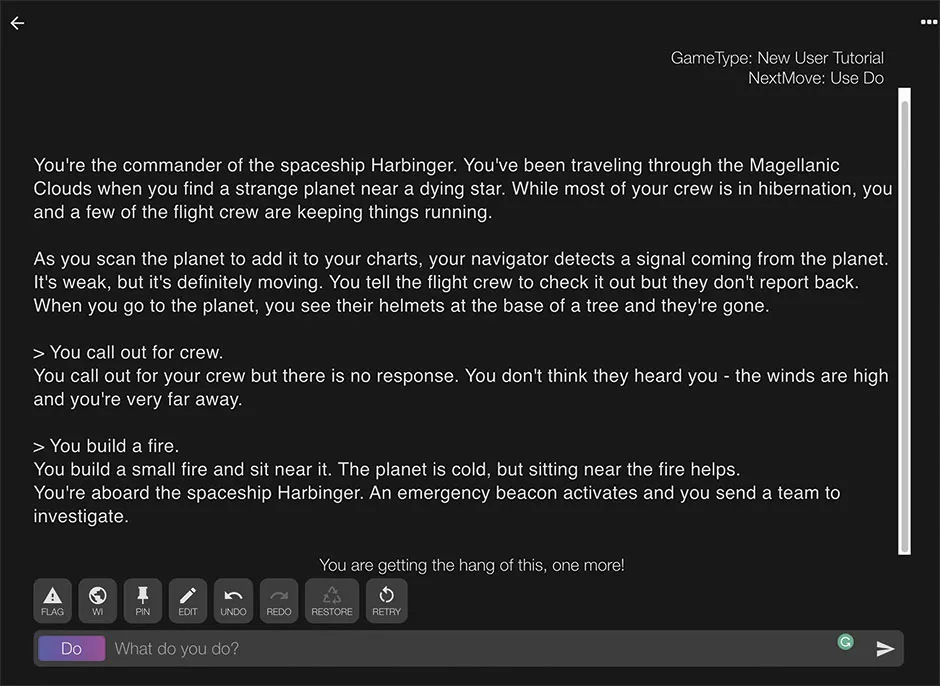

The newer methods create really interesting stories about nearly anything, but they lose coherence really fast because they’re so hard to control. A good, popular example of this is AI Dungeon, where it starts the story and then you take turns with it like you’re playing an old text adventure game.

Both of these examples are interactive story-generation though – they’re telling the story with the person instead of by themselves, which differs somewhat from just a computer telling the story, but they give you a good idea of the types of stories AI is capable of telling.

As a post-grad, you worked on an AI that could play the role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons, how does that fit in?

My work has primarily focused on having just the AI tell more coherent stories. Having an AI actually play Dungeons & Dragons is more of an aspirational goal, something I’d like to see the community come together to tackle – and something that I’ve been chipping away at.

There’s just so much that the computer has to be able to do so that it can play the Dungeon Master. [The Dungeon Master in Dungeons & Dragons runs the game world for other players and create the story details.] The AI needs to be able to understand what story it’s telling, but also understand the parts of the story that the other players are telling.

It needs to make sure everyone else understands the story it’s telling. It needs to be able to create stories that are intrinsically rewarding, so making a story that the players enjoy. This might include creating interesting characters, instead of focusing on extrinsic rewards like collecting experience points by killing a tonne of goblins.

These are just a couple of examples of the hard problems found in playing Dungeons & Dragons that aren’t solved yet, and it’s amazing that humans are able to do it! We can’t even make an AI produce a coherent chapter of a book yet. Basically, language is the real monster we need to understand better.

When will we get an AI Dungeon Master?

To actually see something that acts like a human Dungeon Master? In our lifetime, I don’t know – I’m a little sceptical that it’ll happen. We’ve been making pretty quick progress, but it’s extremely difficult.

Will an AI ever be able to be creative in coming up with a story, or is it only ever able to use the ideas you’ve given it?

If an AI agent comes up with something that’s new and interesting, and then it brings up questions, well, was that the AI’s work or was that the work of the developer or the researcher that created it? There are a lot of legal questions here.

With every AI agent that you make, you’re putting your imprint on it, whether you like it or not. The more of the rule-based side you head towards, the more of your imprint ends up in this agent. So, to ask if an AI can come up with something that’s creative by itself is a tricky question.

Computational creativity is a really fascinating field because there are just so many philosophical questions that we don’t know how to answer. And I’m not a philosopher.

I take it that we’re still some way off having an AI win the Oscar for best screenplay?

While I think it would be great to see creative AI being made, having an Oscar-winning AI just has so many problems, as mentioned above.

The computer is not a living thing and I think that it’s really important for people to realise that computers are not as smart as they think they are. They’re not people, they don’t have agency. They’re just tools that other people have used to work on these things. So I think the best use of creative AI is using it as a tool to augment human creativity.

Computers are extremely good at looking through large amounts of data so they can come up with things that you’ve never seen before, never thought of as being connected. But humans are really good at taking those connecting ideas that the computer might present to them, and running with it.

I told one of my earliest systems to come up with the next sentence in a story. Most of the time it just came up with random, weird things that didn’t work. But then it happened to come with this idea of a horse becoming a lawn chair entrepreneur.

The computer knows nothing about what that means, it’s just spitting out stuff. But you could have a human take that and run with it, maybe they go and make a story about this horse – that would be fantastic.

Humans have this ability to connect these things that the AI comes up with, and I think that’s a really good, symbiotic relationship that needs to be used more.

- This article first appeared inissue 360ofBBC Science Focus Magazine–find out how to subscribe here