To cope with surging populations, city planners are starting to look beneath their feet for space

As the world’s population continues to rise, space is becoming scarcer, and cities are looking for new places to host their residents. For Singapore – the world’s third most densely populated country and home to nearly six million people – the answer is to head downwards.

Climate change and rising sea levels mean that reclaiming land is no longer a sustainable option for Singapore. Instead, the country is looking to create an underground city. Earlier this year, Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority published its draft master plan, setting out what the next 15 years are going to look like.

Read more about future cities:

- The changing face of our smart cities

- Could humans live in underwater cities?

- Human overpopulation: can having fewer children really make a difference?

So far, the equivalent of £10.7m has been invested in the research and development of underground tech. Laws have been changed regarding home ownership, so people only own the land as far down as their basement, to free up space beneath houses for development.

People won’t be living underground at first, the authority says. Instead, the city will start by moving storage, utilities, transport and industrial facilities underground, freeing up space above ground for residential and commercial uses.

Currently, Singapore uses underground spaces for transport and cooling systems, which go down to 20m. A deep tunnel sewage system for transporting waste water and sewage is planned for 20m to 50m.

“For deeper space of more than 100m, more heavy-duty functions such as ammunition storage and caverns for petrochemical storage could be created,” says Sing Tien Foo, director of the Institute of Real Estate Studies at the National University of Singapore. One major planned development is the Jurong Rock Caverns, which can hold about 1.5 million cubic metres of crude oil and petroleum.

Moving transport beneath the surface will help people escape Singapore’s weather

At the country’s airport, Changi, a four-in-one transport hub will host three train depots and one bus depot by 2024, all underground. This will help the country to double its train network by 2030, with all additional railways underground. Moving transport beneath the surface will also help people to escape Singapore’s weather, which is seeing rising heat, humidity and rainfall as a result of climate change.

In order to make the most of its subsurface environment, Singapore first needs to understand what’s down there at the moment. Currently, Singapore’s Building and Construction Authority is developing a 3D geological model using laser scanning, which will be collated into a central database to help map and plan the underground space.

Prof Kevin Curran, a cyber security expert at Ulster University, says that technology is going to be key in allowing this kind of eco-city to develop. For example, air quality will become an important factor that will need constant monitoring, as underground air isn’t circulated as easily as air above the surface. “Sensor-enabled devices are already helping monitor the environmental impact of cities around the world, collecting details about sewers, air quality, and garbage,” say Curran.

Underground cities might have smart rubbish bins, for instance, which send an alert when they need to be emptied, and smart lighting, which only comes on when traffic or pedestrians are approaching.

Although much of Singapore might be underground by 2030, it will be a little longer before people are living there. “Deep underground construction is costly,” says Foo. “There’s complexity associated with access, ventilation and fire safety.

“The use of the underground space for residential and commercial uses has not been planned yet,” he adds, “but the feasibility could be evaluated in the future, if more land is required.”

As sea levels encroach on the land, could we move people to the oceans?

In 2007, Marc Collins Chen was working as the minister for tourism in French Polynesia when reports started to emerge that the Pacific islands would be under threat from rising sea levels in the coming decades. “There wasn’t consensus around when this would happen,” he says. “But there was a sense of doom.”

Today, Chen is CEO of Oceanix, a company based in Hong Kong that’s developing concepts for floating cities. He’s now been working on the problem for 12 years. “If you’re a Pacific Islander and many of your islands are at sea level, you have to look at a solution,” he says.

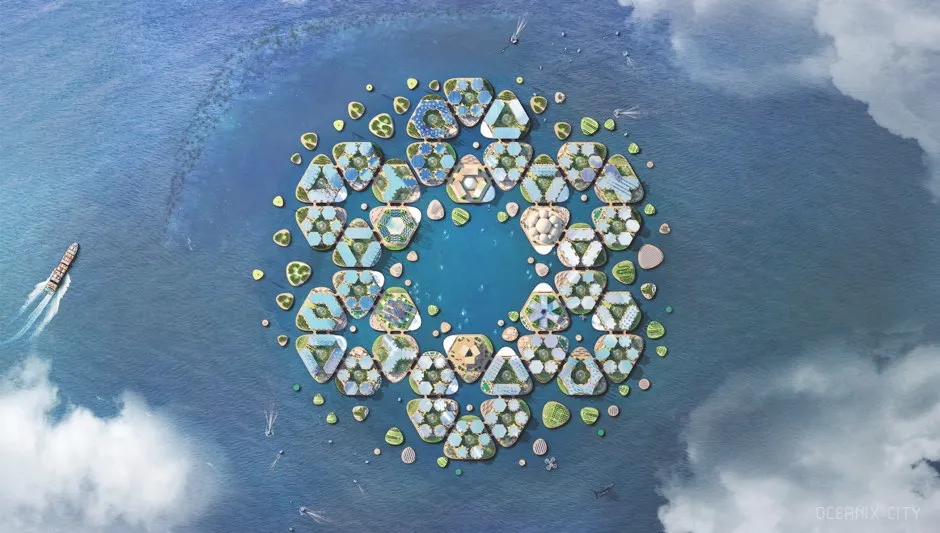

Earlier this year, Oceanix announced a collaboration with the Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and MIT’s Centre for Ocean Engineering, creating a concept for a city of 10,000 people. It was unveiled as part of the UN’s New Urban Agenda, a plan to create ways for the world’s growing population to live more sustainably.

The 10,000 figure is an estimate, says Chen, and the way the city works means it will be able to host as few or as many people as necessary. The city will be made up of floating, roughly triangular platforms, each around two hectares in area and home to 300 people. Each platform, or ‘neighbourhood’, will generate its own renewable electricity from the waves and Sun, and the population can be increased by adding more of these modular platforms.

Alongside renewable energy, the city will grow its own plant-based food, and treat and reuse all waste water. “If you wanted to feed everybody with beef and chicken, you’d need so much surface area and freshwater,” says Chen. “It’d become economically unfeasible.”

The platforms will be secured to the seabed with biorock, which is a material already being used to create artificial reefs around the world. A low-voltage electrical current is passed through a steel frame, which electrolyses the seawater around it and causes charged particles (‘ions’) to build up on its surface, coating the steel in a rocky substance that’s as strong as concrete.

Making sure the cities have a positive impact on the environment is crucial, Chen says. The UN uses ‘ecological footprints’ to measure the impact people have on the natural world, measured in global hectares per person.

At current population levels, our planet has only 1.7 global hectares (gha) of biologically productive surface area per person. At the moment, the UK has a footprint of 7.9 gha per person, which means we’re using more than we have.

As the world’s population increases, we need to be reducing our individual footprints. Chen says that Oceanix could have a footprint of as little as 0.5 gha per person, helping to reduce the strain on our ailing planet.

This might all sound quite far-fetched, but Chen believes it will happen, and soon. The company is aiming to have a prototype of the floating city in place within the next two and a half years, although the location has not yet been pinned down.

- Residents will walk, cycle or boat through the city, with solar-powered ferries transporting them to the mainland

- Villages will be composed of six platforms around a small, central harbour

- A large, protected harbour will be formed in the heart of the city. The six innermost neighbourhoods will include a public square, marketplace and centres for spirituality, learning, health, sport and culture

- All buildings will be lower than seven storeys (to windproof them)and made from locally-sourced materials such as bamboo

- Six villages will connect to form a city of 10,000 residents, spread across 75 hectares

- Individual platforms, or neighbourhoods, will be two hectares in area and home to up to 300 people

- Each neighbourhood will generate its own renewable electricity through technologies such as solar roofs and wave energy converters

Can forest cities help to mop up our pollution?

Traditionally, the more people in a city, the fewer trees there are. To create space for houses, offices and other buildings, nature takes second place. But, if the architect Stefano Boeri has anything to do with it, this will soon be changing.

Boeri has designed a forest city, to be created in the north of Liuzhou – a metropolis in the Guangxi region in southern China. This mountainous area was chosen to be “a city where living nature is totally intertwined with architecture,” according to Boeri.

Instead of completely getting rid of the trees to build houses, the city’s design accommodates the surrounding greenery. Homes and commercial buildings will be covered with trees, with gardens on the balconies of every floor, and rooftops that are home to miniature forests.

“I have been working on the idea of urban forestation for years,” says Boeri. “In those areas of the planet where it is still necessary to build new cities, we are planning real forest cities for a maximum of 150,000 inhabitants.”

The Liuzhou Forest City will be connected to central Liuzhou via a railway line and a road. It will be home to 30,000 people, and include commercial and recreational spaces, two schools and a hospital. On top of this, the vegetation will absorb carbon dioxide and pollutants, as well as releasing oxygen into the atmosphere.

Development is well underway for the forest city. “Our masterplan for a forest city in Liuzhou has been approved by the local government,” says Boeri. Now, the government is starting the process of selling land to interested developers. “The current phase is still ongoing for land selling,” says Boeri.

Building is expected to begin in 2020. At the same time, the firm has replicated the concept in Lishui, a city in the southeast of China. The masterplan has also been given the thumbs-up by local governors here, and the developer is collecting funds to launch the project.

If the Chinese cities prove successful, Boeri hopes that the idea will take hold across the world. “We are developing the same concept in other places with different climate conditions, such as Mexico and north Africa,” he says.

And there is science behind the idea of planting trees to halt climate change. A study earlier this year by scientists at ETH Zurich found that planting at least a trillion trees around the world could lock up 205 billion tonnes of carbon, once the trees are mature, helping to offset the effects of releasing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard