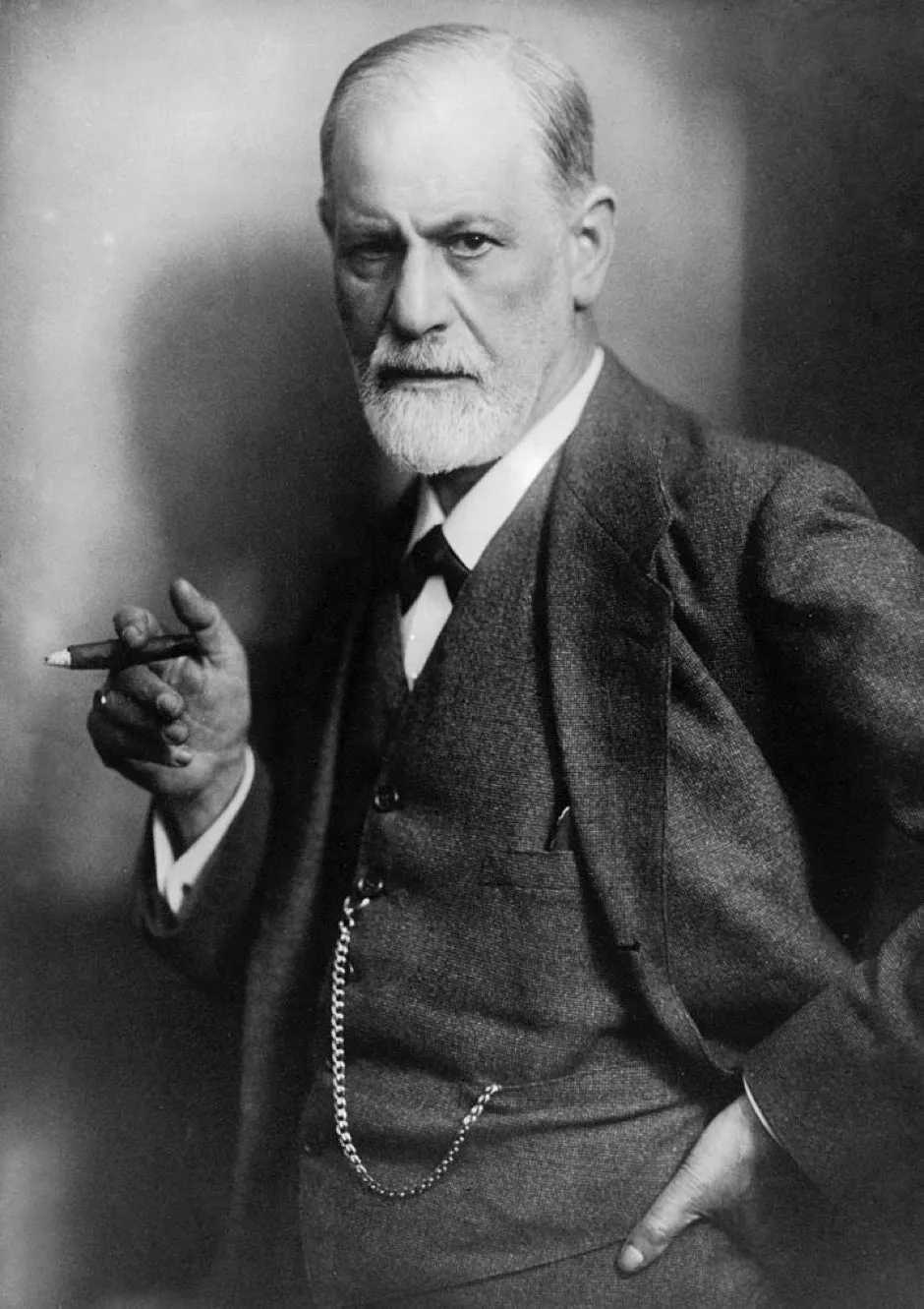

The recurring nightmares of World War I veterans prompted Freud to rethink his ideas about how dreams work, and to establish aversive memories, rather than repressed desires, as the engine of emotional life.

By the 1960’s, veterans found themselves disturbed by waking memories, which they referred to as “flashbacks,” that transported them back in time and assumed the status of truth.

If Freud observed that the tendency to relive traumatic events in dreams “astonishes people far too little,” today we are not just unsurprised that our worst memories reoccur unbidden and without warning—we expect them to.

People often assume that the phenomenon of trauma remains the same over time even if what we call it—shell shock, combat fatigue, PTSD—changes. In fact, the traumatic symptoms of veterans in each war have historically specific features and these gradually evolve and change.

When we speak of someone being “triggered,” we invoke not only Freud’s observations, but also the history of the flashback as it unfolded during the second half of the 20th Century. How did the night-time recollections of WWI veterans seep into waking life, and how did flashing back come to define the experience of trauma?

Flashbacks are waking memories with the vivid and hallucinatory properties of dreams; they produce an altered, trance-like state, during which current realities disappear and volition is suspended. Flashbacks became a feature of war memory during the Vietnam era and it is worth noting that the symptom was rarely experienced by veterans of earlier wars.

Read more about treating mental illness:

- Sleep, drugs and mental health: how altered states of consciousness could keep us happy

- MDMA may help psychotherapists to treat post-traumatic stress disorder by rewiring patients’ brains

That said, the flashback, understood as a psychological phenomenon, has roots in earlier clinical experiments on traumatised soldiers. During and after WWII, for example, military psychiatrists used barbiturates to facilitate intense recollections of combat.

In the Vietnam era, such memories were reclaimed by anti-war veterans, who politicised the effects of trauma on the soldier’s consciousness. In these experimental settings, where the war memories of soldiers were retrieved—and sometimes manufactured—the flashback took shape.

During World War II, an epidemic of mental illness among soldiers combined with a shortage of trained professionals to produce a mental health crisis in the military. This crisis, in turn, proved a fertile context for clinical innovation and laid the groundwork for the expansion of professional psychology in the decades following the war.

Psychotherapy under sedation—also called “narcoanalysis” and “narcosynthesis”—was an experimental treatment used to treat soldiers with what were known as “conversion symptoms,” like paralysis, stuttering, and mutism.

Faced with many soldiers who were incapacitated by these symptoms and the urgent need to return them to combat as quickly as possible, therapists used drugs to enable a rapid form of talk therapy. As historian Alison Winter puts it, WWII became “for chemical psychotherapy what World War I had been for psychoanalysis.”

During psychotherapy under sedation, the traumatised soldier received a barbiturate injection that set him on the path to sleep. When it worked well, the drug loosened the patient’s tongue: as he became sleepy, he spoke more openly about his thoughts and feelings, and became more receptive to the prompts and suggestions of the therapist.

During this brief, unguarded phase, the therapist encouraged the patient to relive the original trauma as if it were happening again in the present moment and, in doing so, produced a cathartic release of repressed feeling—what was termed an “abreaction.”

Read more about mental health:

- Can we stop male suicide?

- Raising awareness of mental health is all well and good, but the hows and whys are important too

Therapists went to great lengths to create the experience of reliving, and when a patient did not readily recall a traumatic event they would simulate it for him. Psychiatrists Roy Grinker and John Spiegel, who pioneered the technique of narcoanalysis while treating US soldiers in North Africa, described staging elaborate reenactments in which they played the “role of a fellow soldier.”

Even patients who were initially resistant often responded to such simulation by re-experiencing the scene of war with a terrifying intensity that Grinker and Spiegel found “electrifying to watch.”

Psychiatrists who practiced narcoanalysis were frank about the fact that they sometimes suggested fictions in order to cure a soldier’s traumatic symptoms. British psychiatrist William Sargant noted that in some instances, drugged patients were not encouraged to recall their earlier experiences but rather to imagine new ones that were similar to the traumatic event.

In some acute cases, he writes, “quite imaginary situations to abreact the emotions of fear or anger could be suggested to a patient under drugs.” Practitioners agreed that imagined experiences worked as well as—sometimes even better than—actual experiences to produce the desired effects.

Such clinical experiments walked a fine line between memory retrieval and memory production, paving the way for brainwashing experiments of the Cold War.

Focused on belief, affiliation, and identity, Cold War militarism was in large part ideological, and the process of changing minds was perceived as indispensable to national security.

In this context, WWII-era experiments in healing were repurposed as forms of military aggression that targeted the mind. Psychological warfare weaponised memory, using drugs, hypnosis, and talk to implant false memories and beliefs; techniques engineered to rebuild the human personality in the aftermath of war now served as a means to destroy it.

Against the background of a history of psychiatric experimentation on soldiers, anti-war veterans of the Vietnam era reclaimed their own traumatic symptoms and placed them in the service of war resistance. Activist veterans had a hand in popularising the flashback as they wrested their memories, and the authority to interpret them, from the therapeutic establishment.

In the autumn of 1970, members of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War invited psychiatrist and writer Robert Jay Lifton to join the informal conversations, or “rap sessions,” that they had begun holding with returning soldiers.

In these intense discussions, veterans talked with one another about their experiences in Vietnam and some of the difficulties they had returning to civilian life. Lifton was delighted by the invitation, which allowed him to revisit research that he had conducted many years earlier while serving as a psychiatrist for the US Air Force.

During the summer of 1953, Lifton had traveled by ship from Inchon to San Francisco with 442 American soldiers who been held captive in Korea. The two-week voyage gave military and psychiatric professionals a chance to question returnees in order to understand what Lifton described as “a large-scale, carefully organised, and coercive program of political indoctrination.”

Onboard the USS General Pope, Lifton conducted individual interviews and led group therapy sessions. It is hardly surprising that returnees, who had endured intensive interrogation in Korea, viewed Lifton with suspicion, and he found his shipboard sessions frustrating and unproductive.

Years later, he was eager for another chance to explore the symptoms of war trauma, this time in the company of fellow activists.

Therapists and veterans were equal participants in the rap sessions, and they all regarded talk about trauma as a means to political action. Activist veterans worked with therapists to remember their war experiences. Frequently, these memories involved crimes that they had committed against the people of Vietnam.

Learn more about the Vietnam war fromHistory Extra:

Veterans then went public with these memories, narrating their war crimes in public hearings, and staging reenactments of their brutal assaults on Vietnamese villages in performances that shocked passersby.

During and after World War II, abreaction was a clinical goal, and therapists found innovative ways to encourage veterans to relive their war experiences in twilight sleep. In the Vietnam era, however, such intense recollections were perceived not as a way to cure trauma but as the veteran’s most durable symptom.

Intrusive recollections came upon the Vietnam veteran suddenly, outside of a clinical environment. Routine sights and sounds provoked memories that sometimes led a veteran to “go berserk”—losing control and acting as if he were still in a war zone.

In staged hearings and guerrilla reenactments, veterans turned flashbacks into a type of political performance, bringing repressed knowledge of the war to public consciousness.

Eventually, the radical therapists who participated in the rap sessions developed the diagnostic category of post-traumatic stress disorder, which was adopted by the American Psychiatric Association in 1980. As codified by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III), “re-experiencing the traumatic event” is one the disorder’s chief symptoms.

In the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, we recognise the innovations of WWII-era psychiatrists, who used barbiturates to help soldiers relive trauma, as well as the activism of Vietnam veterans who performed their traumatic memories in an attempt to stop the war.

Today, clinicians use Virtual Reality (VR) therapy to treat veterans who suffer from PTSD. The system “Bravemind,” funded by the US Army, is an immersive 3D surround that simulates generic scenes from recent American wars in Afghanistan and Iraq using not only images but also sounds, smells, and tactile sensations.

Read more about VR and mental health:

During treatment sessions, clinicians employ what is called a “Wizard of Oz” control panel to customise the intensity and pace of the scene and modulate the recreated experience in real time.

VR therapy, which uses simulation to trigger aversive memory in the name of healing, is a contemporary, high-tech version of psychotherapy under sedation. Like earlier treatment, this type of therapy assumes that traumatic memories will return, and that this recurrence is both a symptom of emotional disorder and a means to rehabilitation.

Such experimental treatment reminds us that the nature of remembering, and the afflictions associated with it, are not outside of our control. To the contrary, the history of the flashback demonstrates, in ways that may surprise us, that traumatic memory is subject to reinvention as we continue to study, interpret, and manage the effects of war on the mind.

Fighting Sleep: The War for the Mind and the US Military by Franny Nudelman is out now (£14.99, Verso).