‘Nature, red in tooth and claw’ – the most memorable metaphor of Charles Darwin’s natural selection. Or is it? The poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson coined that phrase nine years before On the Origin of Species appeared, and was referring to earlier ideas about evolution. Perhaps Darwin was not quite as revolutionary as he’s made out to be!

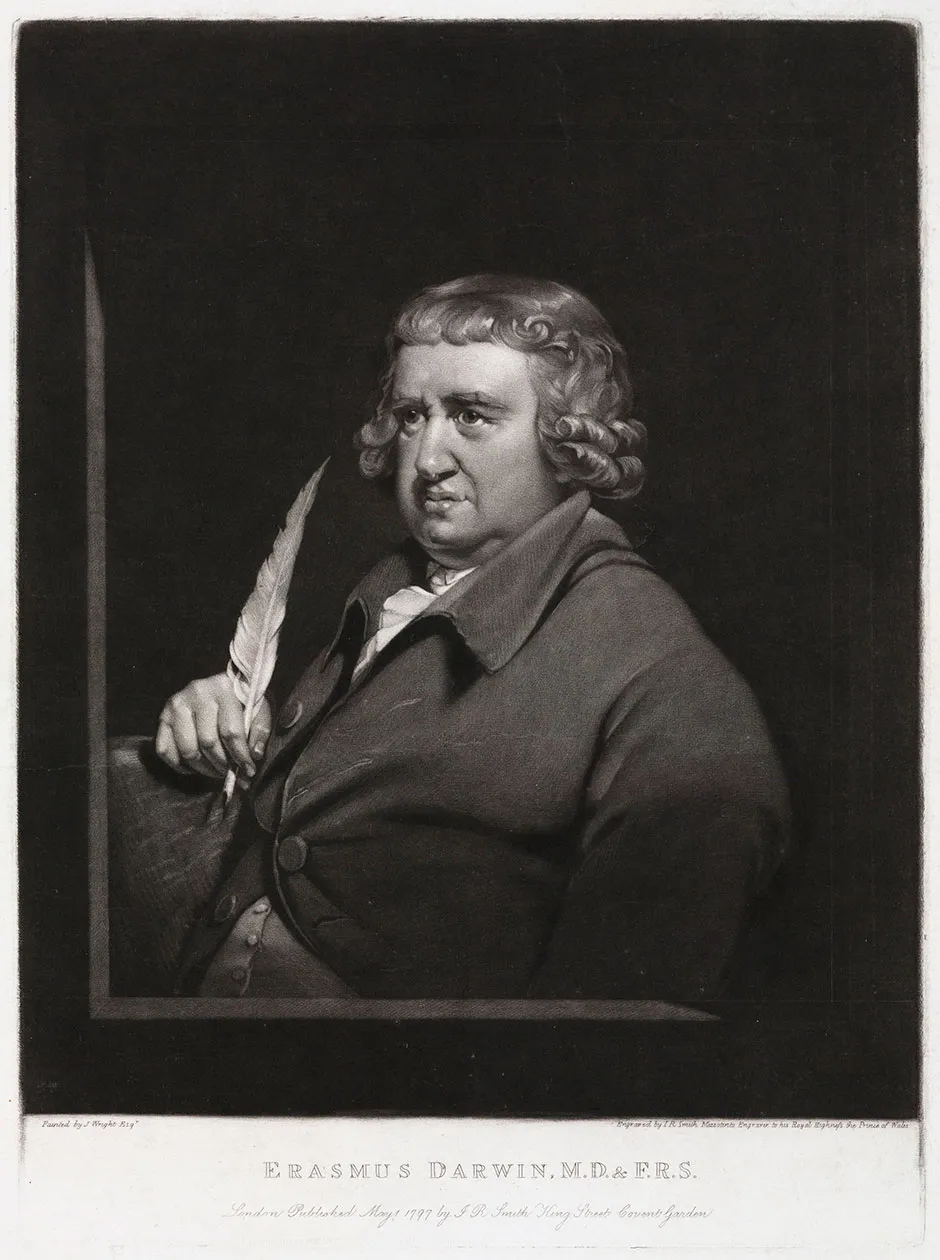

One crucial predecessor was Charles’s grandfather, Erasmus (1731-1802). A renowned physician, he played a major role in British industrialisation and wrote several best-selling poems about science.

More surprisingly, he was a political radical who supported the French Revolution and taught that human beings were not a special creation, but the latest outcome of long developmental processes originating in a tiny speck of life beneath the sea.

Read more about Charles Darwin's evolution:

- How an extraordinary letter to Darwin spotted industrial melanism in moths

- Is it time to drop Darwinism?

Darwin described nature as ‘one great slaughterhouse, one universal scene of rapacity and injustice’ – but those are Erasmus’s words, not Charles’s. It was Erasmus, not Charles, who wrote: ‘The final cause of this contest amongst the males seems to be, that the strongest and most active animal should propagate the species, which should thence become improved.’

Although he died before Charles was born, Erasmus clearly exerted a strong influence.

Charles could not escape his Darwinian heritage. Afflicted with the family’s large nose and his grandfather’s stammer, he was never allowed to forget Erasmus’s dire warnings about inherited alcoholism.

Moreover, critics repeatedly reminded him about Erasmus’s notoriety and his dubious distinction of having a book on the Vatican’s banned list. Like Erasmus, Charles attracted hostility by challenging orthodox views of God, although both denied being irreligious.

Another obvious bequest was Charles’s abhorrence of the slave trade. Erasmus’s poems are not to everybody’s taste, but he consistently supported abolition:

E’en now in Afric’s groves with hideous yell

Fierce SLAVERY stalks, and slips the dogs of hell…

Steeped in this family aversion, Charles responded angrily to slavery throughout his life. Landing in Brazil, he was appalled to witness atrocities at first hand. ‘The extent to which the trade is carried on,” he wrote in his diary; “the ferocity with which it is defended; the respectable (!) people who are concerned in it are far from being exaggerated.’

Charles studied his grandfather’s medical manual Zoonomia, trawled through family papers to write his biography, and annotated his poetry. He borrowed for his own notebook Erasmus’s account of a wasp tearing the wings from a fly so that it would be easier to carry.

Read more about evolution:

- Mammal evolution: How ancient fossils are revealing the secrets of our earliest ancestors

- 10 weird ways humans have influenced animal evolution

He read about the benefits of close observation, about male features suited for procuring mates, such as a stag’s branched horns or a quail’s spurs, and about Erasmus’s insights into human behaviour gained from watching elephants pick up coins, squirrels run around their cages and birds line their nests.

Charles was thinking about evolution several years before he travelled on the Beagle.

During his truncated spell as a medical student, he explored the revolutionary implications of Erasmus’s Zoonomia, with its controversial suggestion ‘that in the great length of time, since the Earth began to exist … warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament … possessing the faculty of continuing to improve by its own inherent activity, and of delivering down those improvements by generation to its posterity…

This claim was triply offensive: it contradicted the Bible by extending the age of the Earth; it implied that after some unspecified act of creation, living beings could be produced without divine intervention; and it maintained that the living world had developed gradually, rather than being created by God exactly as it is now.

Soon after returning home, Charles opened a new notebook with an underlined title: ‘Zoonomia’. He started by jotting down notes on generation, referring himself to Zoonomia’s arguments. By page four, he was speculating how a species might adapt in response to a changing environment, and then he sketched his first version of an evolutionary tree.

Erasmus provided his most detailed account of evolution in his final poem, The Temple of Nature, evocatively subtitled On the Origin of Society. As if writing a poetic predecessor to On the Origin of Species, he remorselessly accumulated examples rather than supplying logical proofs – precisely the rhetorical device adopted by Charles.

He fretted over redundancies such as male nipples, wondering if they might be vestigial traces left over from earlier transformations. Like Charles, Erasmus saw no final purpose in the processes of change, no overall divine plan.

His absentee God gave the first spark of life to matter, but then withdrew, standing back as living creatures evolved according to natural laws.

In his autobiography, Charles explained that reading Thomas Malthus yielded key insights into the competitive struggle for survival during scarce resources. Malthus’s Essay first appeared in 1798, when Erasmus was working on The Temple of Nature, in which he interpreted the natural world as a constant battle between opposing forces of good and evil.

In couplet after couplet, wolves tear apart innocent lambs, eagles swoop on helpless doves, and sharks gobble up shoals of fish. Death, warfare and disaster, Erasmus argued, are essential for preventing a population explosion that would outrun the world’s resources. In his personal copy, Charles marked these Malthusian lines:

From Hunger’s arm the shafts of Death are hurl’d,

And one great Slaughterhouse the warring world!

The extent of Erasmus’s influence must remain speculative, but Charles may well have leant on his grandfather’s ideas more heavily than he was willing to admit. Who can know if, as he aged, he looked in the mirror (both literally and metaphorically) to see his grandfather staring back at him?

In On the Origin of Species, Charles glossed over the thorny problem of life’s origins – but he could never escape his own origins as Erasmus Darwin’s grandson.

Erasmus Darwin: Sex, Science and Serendipity by Patricia Fara is out now (£12.99, Oxford University Press).