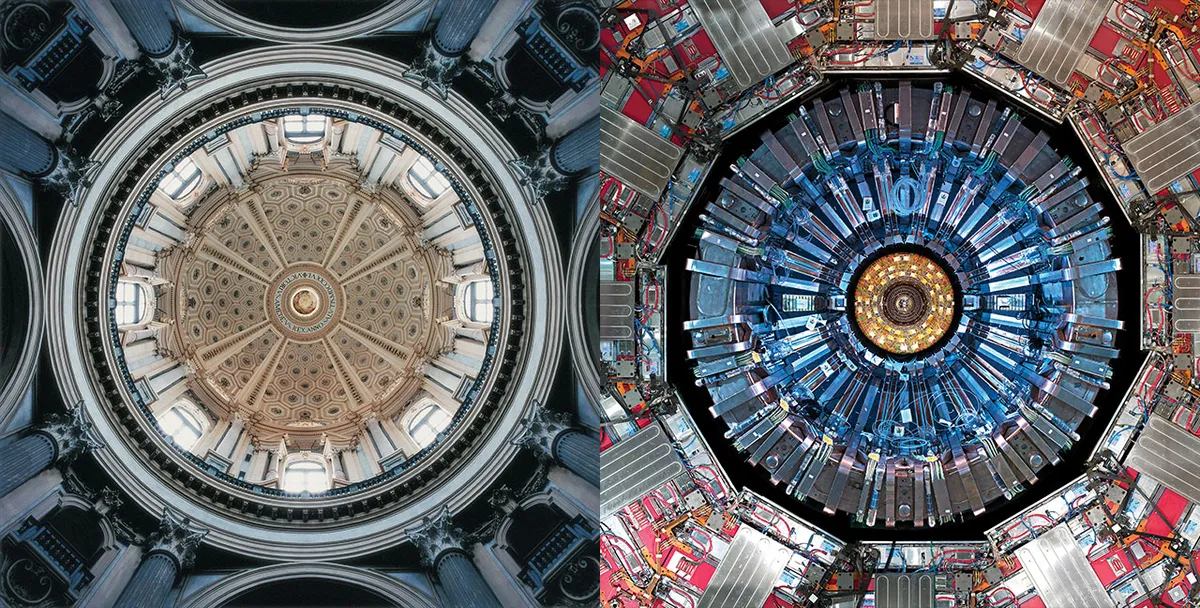

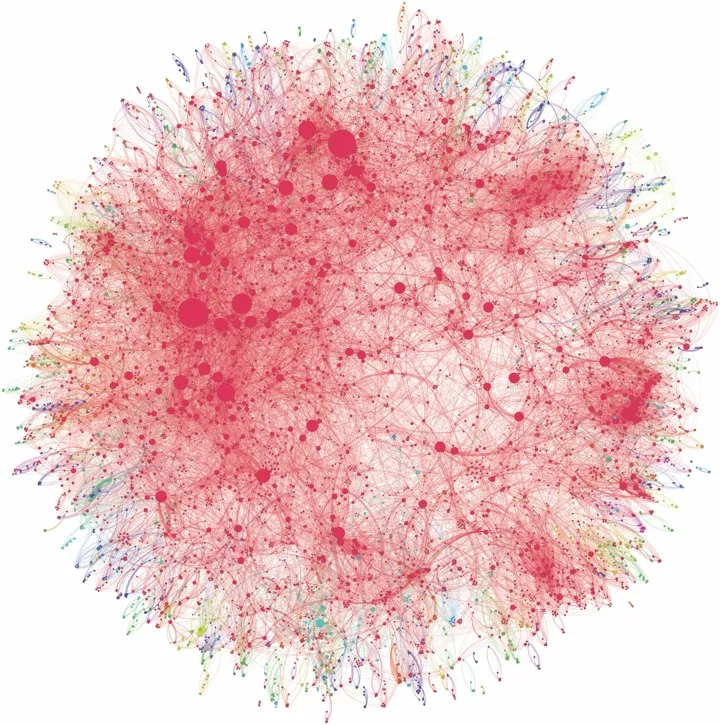

The circle has been adopted in every conceivable domain of human experience, from money and art to architecture and religion. The interesting question is: why? The circle is omnipresent in nature, but can this fact alone explain its central role in the cities we build, the objects we design, the visual symbols we create, and the numerous layers of cultural meaning we construe?

A preference for circular shapes is deeply ingrained in all of us from birth. A 2011 eye-tracking study found that at five months of age, before they utter a word or scribble a drawing, infants already show a clear visual preference for contoured lines over straight lines.

Over the last century, researchers on human perception have tried to explain our innate propensity for circular and curvy shapes. In a 1921 study conducted by the Swedish psychologist Helge Lundholm, subjects were asked to draw lines representing a set of emotional adjectives. While angular lines were used to depict adjectives like hard, harsh and cruel, curved lines were the popular choice for adjectives like gentle, quiet and mild. Over the years, other studies trying to associate feelings with types of lines have corroborated Lundholm’s findings.

Typography has been the target of a similar analysis. A study conducted in 1968 by psychologists Albert Kastl and Irvin Child indicated that people associate positive qualities like ‘sprightly’, ‘sparkling’, ‘dreamy’, and ‘soaring’ with curved, light, and possibly sans-serif typefaces. This could in part explain, to many graphic designers’ frustration, the wide-ranging popularity of the Comic Sans MS typeface.

In a seminal paper published in 2006 in Psychological Science, cognitive psychologists Moshe Bar and Maital Neta conducted an experiment in which 14 participants were shown 140 pairs of letters, patterns, and everyday objects, differing only in the curvature of their contour. The results were not completely surprising: participants showed a strong preference for curved items in all categories, particularly when it came to real objects.

To better understand this bias, the same pair of scientists conducted another study one year later, this time by mapping the cognitive response using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The results were quite conclusive. Sharp-cornered objects caused much greater amygdala activation than rounded objects. A well-studied region in the temporal lobe of the brain, the amygdala’s primary function is to process stimuli that induce fear, anxiety, and aggressiveness and to deal with the resulting emotional reactions. In other words, angular shapes tend to trigger fear and therefore aversion and dislike. Moreover, the authors of the study noted that “the degree of amygdala activation was proportional to the degree of angularity or sharpness of the object presented, and inversely related to object preference.” There are, of course, obvious exceptions to this response. People do not like some curved objects, such as snakes, and do appreciate some angular objects, such as chocolate bars. But as the authors point out, these objects have a “strong affective valence, which can override the effects of contour and dominate preference.”

Most of the research in this area seems to point out an evident truth: we prefer shapes and objects that evoke safety and are not so fond of objects with sharp angles and pointed features, as they suggest threat and injury: think of the thorns and spines of a plant, the sharp teeth of an animal, or the cutting edge of a rock. This preference might still prove prudent in an urban world lacking natural threats but abundant with man-made ones. As the ultimate curvilinear shape, the circle embodies all of the attributes that attract us: it is a safe, gentle, pleasant, graceful, dreamy, and even beautiful shape that evokes calmness, peacefulness, and relaxation.

The second evolutionary explanation for our round-shape proclivity is rooted in the idea that human faces and the emotions they express rely on simple geometric shapes. Just think of the number of expressions that emoticons can represent using very rudimentary configurations. This idea touches on deep survival instincts and social behaviour. In 1978 psychologist John Bassili conducted an experiment in which he painted the faces and necks of several actors and actresses black and then applied one hundred luminescent dots. Participants were then asked to assume different expressions, such as ‘happy’, ‘sad’, ‘surprised’, and ‘angry’. In the final video recording, with only the luminescent dots visible, the outcome was quite revealing: while expressions of anger showed acute downward V shapes (angled eyebrows, cheeks, and chin), expressions of happiness were conveyed by expansive, outward curved patterns (arched cheeks, eyes, and mouth). In other words, happy faces resembled an expansive circle, while angry faces resembled a downward triangle.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the warm, positive emotions elicited by a circular shape could have their basis in our attraction to the roundness of an infant’s face. The evolutionary advantages of these feelings are obvious, particularly since previous studies have indicated an adult preference for infants with prominent rounded features. This also explains a known cognitive predisposition called the ‘baby-face bias’, a tendency to perceive adults with neotenous facial features—large eyes, a rounded face, and a high forehead—as being more naive, honest, and innocent. The dichotomy of circular, happy faces versus triangular, angry faces seems to be rooted in two primordial human imperatives: our need to read our fellow humans’ facial expressions and our need to detect threats as quickly as possible.

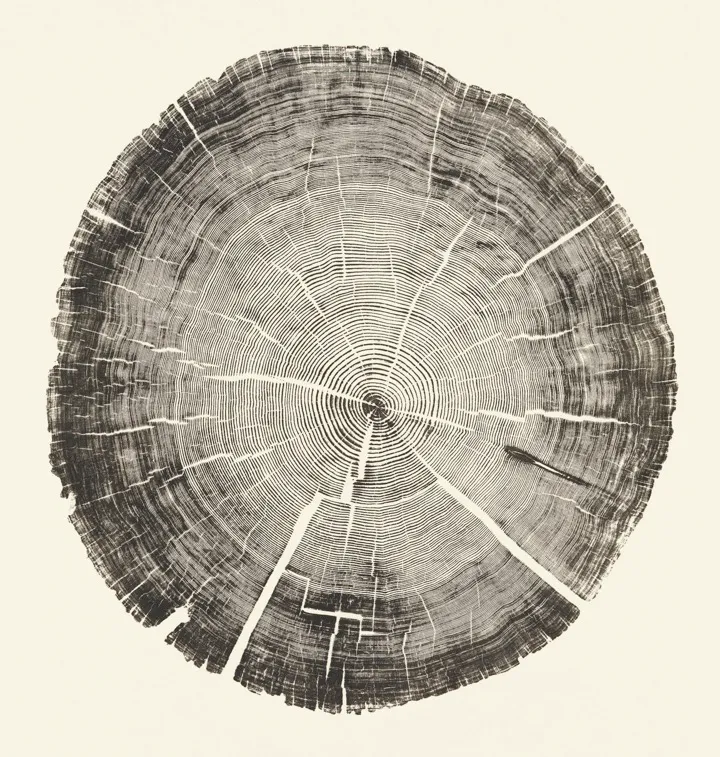

The third and last explanation for the universal allure of the circle might be rooted in our own visual cognitive apparatus and the way we view the world around us. The human eye is undoubtedly a fascinating object of study: an organ so complex and demanding that half of our brain is dedicated to processing visual perception. These spherical orbs abound with circularity, their most noticeable elements being the iris and pupil, responsible for filtering light into our retina. Most important, such spheres create a natural circular frame for our visual field, which on its own could substantiate an innate preference for matching geometric shapes. This could also explain the almost hypnotic effect of concentric circles: one of the oldest configurations of the circle, and the subject of numerous optical illusions.

In the second volume of Modern Painters (1843–60), English art critic John Ruskin proposes six main attributes of beauty. In what seems like an uncanny argument for the inherent attractiveness of the circle, Ruskin’s list includes the following elements: (1) infinity, (2) unity, (3) repose, (4) symmetry, (5) purity, and (6) moderation. Ruskin’s assessment of beauty is not just in line with some of the circle’s traditional associations. As we know today, Ruskin’s list appears to shed light on a set of universal, deeply ingrained perceptual preferences.

I began by asking if the broad cultural adoption of the circle could be justified entirely by its omnipresence in nature. The answer should be evident by now: the circle’s natural ubiquity has certainly been a contributing factor, but not the decisive one. The more we dig into our shared cognitive biases, the more we recognise that the copious layers of cultural meaning we have added to the circle through the ages are ultimately grounded in an instinctive evolutionary proclivity. As with many other areas of human aesthetics, the circle’s inescapable beauty seems deeply rooted in our biology.